Finally, we’re talking about the heyday of Hong Kong Type.

Our golden era.

We should start with James Legge.

Legge, our guardian.

You could also say he’s our stepfather.

It’s better to say adoptive father.

Why always use “father” as the starting point of inheritance? Can’t we talk about the mother of Hong Kong Type?

To say father or mother are merely metaphors.

But the metaphorical meaning of father and mother do differ.

Miss Talented, you’re really persistent.

Legge and other creators are men, calling them mothers seems a bit strange.

Unless we’re talking about masculinity or femininity.

What do you mean?

Masculinity stands for domination, femininity for integration.

So, you’re saying Legge represents femininity.

Because he adores Chinese culture?

Through him, the possibilities for dialogue, communication, and understanding between the East and the West are opened up.

Don’t speak too fast, I’m having trouble keeping up.

Alright, let’s start over again.

James Legge, a Scotsman, had been intelligent and studious since childhood. With his extensive knowledge and strong memory, especially in Latin, he excelled academically and was admitted to the King’s College of Aberdeen, which had a history of three hundred years, the precursor of the University of Aberdeen.

His faith belonged to the autonomous and anti-authoritarian Scottish non-state rule Congregational Church.

Compared to his predecessor Dyer from Cambridge University, Legge had more of a scholar’s character.

Or might be better described as the temperament of an intellectual.

However, he lacked the kind of fervent vision of evangelism.

He was a down-to-earth person.

Seemingly not too interesting.

As though he was not highly valued.

Or nearly forgotten by the world.

Despite this, in his later years, he was recognized as a leading Sinologist of his time.

In January 1840, 25-year-old James Legge and his newlywed wife Mary arrived in Malacca. While immersing himself in the work of the mission station, he was also studying Chinese at the Anglo-Chinese College.

For the first time, Legge was introduced to Confucian classics, and he was immediately inspired to translate the Four Books and Five Classics, and even the Thirteen Classics, into English.

It was really quite ambitious for a young man.

As history has shown, Legge did not let down the mission he voluntarily undertook in his youth.

The connection between Legge and Chinese can be traced back to his childhood when he saw on his father’s bookshelf Chinese missionary pamphlets compiled and published by the missionary pioneer William Milne in Malacca.

It might have been Discussions Between Zhang Yuan and His Friend or Monthly Record of the Observation of Worldly Customs.

Being an avid reader, he was drawn to the strange and mysterious characters printed on the slightly yellowing pages.

Why did his father have Milne’s Chinese publications?

Because both of their families were living in Huntly, Scotland, and they both belonged to the local Congregational Church, so they were already acquainted.

Do you remember the children sent back to their country after Milne’s death? One of the boys had grown up, inheriting his father’s aspiration and joined the London Missionary Society, traveling eastward along with Legge.

He was William Charles Milne, who later got involved in the translation of the Delegates’ Version of the Bible.

What a wonderful turn of events!

They would say it’s God’s arrangement.

Therefore, it can be said that James Legge has had an early foundation in Chinese.

In Eastern terms, it would be considered a past-life connection.

Legge wouldn’t necessarily disagree, but he would say it’s the interconnection between cultures, or the shared origin of beliefs.

This was his view in his later years, when he was young, he probably just had a faint premonition.

At that time, many Western missionaries looked down on Chinese culture, considering China a tyrannical, backward, superstitious, idol-worshiping nation.

They came with the holy mission of saving the Chinese people.

Legge was not without this typical Western sense of superiority. However, he also believed that Western missionaries should fully understand Chinese culture before preaching to the Chinese. To understand Chinese culture, one must start from the oldest traditional classics, which have dominated the thoughts and systems of the Chinese for three thousand years. Only in this way can one achieve true understanding and preach most effectively.

This is what is meant by “knowing oneself and knowing the other.”

What sets Legge apart is that in addition to missionary purposes, he seemed genuinely believe there was something within the Chinese classics that was worth exploring and learning about, something that could cause Christians to reflect.

Alongside missionary James Legge, a glimpse of translator and scholar James Legge also emerged.

Consequently, Legge collaborated with Ho Tsun-shin, a fellow student at the Anglican-Chinese College, to attempt a translation of a part of the Book of Documents, but this was shelved due to inadequate proficiency in Chinese.

He found the translation project to be more challenging than he thought.

The giant spirit of Chinese culture was also stronger than he anticipated.

At that time, he did not know he would spend his entire life battling with this giant spirit.

The London Missionary Society, as always, did not support their members spending time on non-missionary tasks. To prove that academic research would not interfere with his missionary work, Legge got up at three o’clock every morning to study the Chinese classics until dawn, and then spent his days fulfilling his duty.

He kept this habit of studying early in the morning for the rest of his life.

Ho Tsun-shin was the first Chinese friend of Legge. When Ho was young, he followed his father, who was a typographer then, to Malacca and was educated at the Anglo-Chinese College where he excelled in English.

Later on, Ho Tsun-shin accompanied Legge to Hong Kong to spread the gospel, changing his name to Ho Fuk-tong, becoming the second Chinese pastor after Liang Fa.

Ho Fuk-tong had many children, some of whom became well-known social figures. Among them, his fifth son, Ho Kai, went to England to study medicine, and was appointed as a member of the Legislative Council upon his return to Hong Kong. He was knighted and became one of the early Chinese leaders in Hong Kong.

That brings us to Hong Kong.

In September 1843, missionaries from the London Society gathered in Hong Kong to discuss the allocation of work in the newly opened ports after the signing of the Treaty of Nanjing.

Legge, at the age of 27, moved to this newly established city with his wife, two young daughters, and other teachers and students from Anglo-Chinese College.

At that time, the north shore of the island was desolate and uninhabitable. The British reclaimed land from the narrow coast, opened roads on the steep slopes, and established the city of Victoria.

In the early days of the port’s opening, living conditions on the island were very poor. Epidemics of tropical diseases were rampant, many died, and security was extremely bad, with pirates occasionally coming ashore and ransacking homes.

Yet, Legge had an incredibly resilient character. No matter whether he encountered illness, injury, or setbacks in life, he was able to recover quickly.

He purchased land between the newly opened Staunton Street, Aberdeen Street, Hollywood Road, and Elgin Street, and established a mission station with facilities that included residences for missionaries, school classrooms, student dormitories, libraries, and printing houses.

The moveable type, typecasting tools, and printing machines for the Anglo-Chinese College print office would not arrive in Hong Kong from Singapore until 1846.

In September 1847, Richard Cole, a professional printer who transferred from the Chinese and American Sacred Classic Book Establishment in Ningbo, took office, and the type-casting project left by Samuel Dyer was fully launched again. By 1851, the two sets of movable type were generally completed.

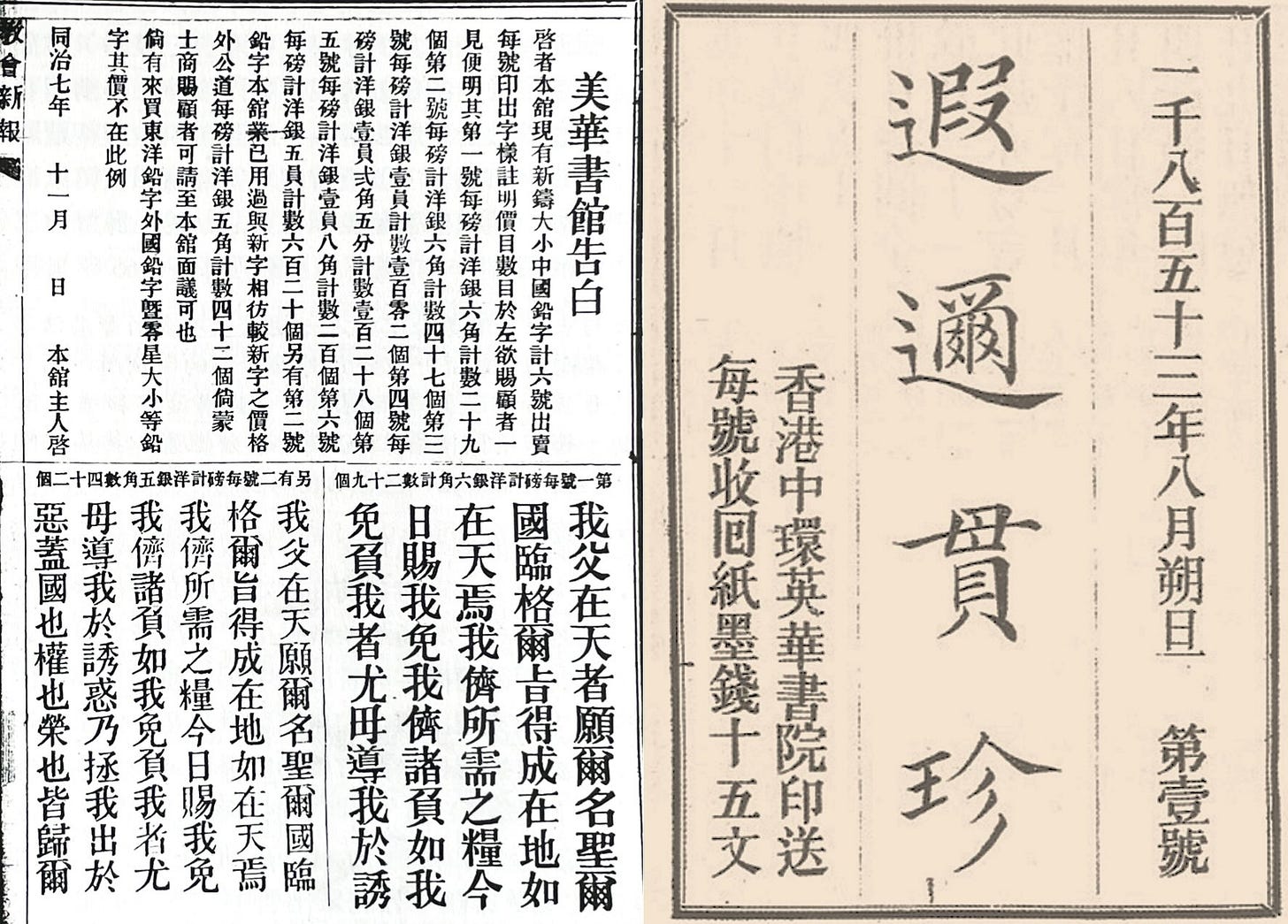

After completion, the movable type was immediately put to use. The primary task was to print the Delegates’ Version of the Bible, and the second was to publish the comprehensive journal Chinese Serial.*

I have seen Chinese Serial in the library. The content is very interesting, with few missionary articles, mainly focusing on history, science, geography, medicine, knowledge and current affairs.

Yes, we were very happy to print this book.

This journal was first issued in 1853 and ceased publication in 1856. It was basically a monthly magazine with a print run of 3,000 copies per issue. The target readers were Chinese in Hong Kong and other trading ports. Its editors were the son and son-in-law of Medhurst, Walter Henry Medhurst and Charles Batten Hillier, both of whom were officials of the colonial government. Legge also had a part in it.

Compared with the early Chinese magazines like Milne’s Monthly Record of the Observation of Worldly Customs and Medhurst’s Monthly Record of Selected Digest, it had richer content, more mature editing, and of course, great improvements in printing.

The most important book you’ve ever printed must be James Legge’s Chinese Classics, right?"

You’re absolutely right! It was an unforgettable experience in our life!

However, before we start talking about the printing of Chinese Classics, we need to review the circumstances under which Legge conducted this private research, which was not endorsed by the London Missionary Society.

After settling in Hong Kong, Legge took on many roles. He set up the preaching station, reopened Anglo-Chinese College, engaged in local evangelism, served as a pastor for Brits in Hong Kong, managed a printing press, and supervised typography. He also promoted free public education and contributed to the establishment of the Central College.

In his personal life, his wife Mary died in childbirth in 1852. The following year, he sent his three daughters back to Britain, only to soon receive the news of the death of his third daughter, Emma. In 1858, he returned to England to remarry and came back to Hong Kong in 1859 with his new wife Hannah, stepdaughter Marian and his own daughters Elisa and Mary.

Despite the trials and tribulations of these years, they did not erode his determination to translate Chinese Classics.

Relying on his unchanging habit of reading early in the morning, he remained unwavering and diligent.

The distance from the original vow was exactly a span of 20 years.

By the way, all the publishing costs of Chinese Classics were sponsored by Robert Jardine of Jardine, Matheson and Co., and the London Missionary Society didn’t pay a penny. They only allowed Legge to pay to use the facilities of Anglo-Chinese College Printing House.

The printing of the first volume began in 1860 and was officially published in 1861. The first volume includes Confucian Analects, The Great Learning, and The Doctrine of the Mean. The second volume is The Works of Mencius, which together constitute the Four Books.

The typesetting method can be considered a pioneering act at the time. Each page is divided into three parts: top, middle, and bottom. The top part is the original text of the classic, printed from right to left in the large Chinese typeface by Dyer; the middle part is English translation, printed from left to right; the bottom part is the annotation in mixed small Chinese and English fonts. This layout is both complex and clear, and it was the first time this kind of mixed typesetting style was ever used.

This could only be achieved through the development of Chinese movable type.

Legge fully realized Dyer’s vision on this.

Apart from printing our own products, we also spread outside. Selling movable type became the main source of income for the Anglo-Chinese College. Selling a full set of type would cover the annual expenses of a mission station.

In the early days of relocating to Hong Kong, the London Missionary Society didn’t think much of the existence of the Anglo-Chinese College Printing House. They even considered terminating it or relocating it to other ports. But once they started making big money from selling movable type, their perspective on the printing house completely changed.

The Chinese printing industry in all of Hong Kong began to rely on us.

Not to mention the Chinese announcements from the Hong Kong Government. The two earliest local English newspapers, The China Mail and The Daily Press, both purchased Anglo-Chinese College typefaces to have on standby. Later on, the two newspaper offices published their own Chinese newspapers - The Hong Kong Chinese Daily and The Hong Kong Chinese and Foreign News. Of course, they also used our typefaces.

There’s also an interesting book. It’s an account by Hong Xiuquan’s cousin, Hong Rengan. It's called The Visions of Hung Siu-Tshuen, and Origin of the Kwang-Si Insurrection, written by Swedish missionary Theodore Hamberg. The book was published by The China Mail, using a mix of Chinese and English typefaces.

Hong Rengan stayed in Hong Kong for a few years, right?

You know too? Hong lived in Hong Kong for three years from 1855 to 1858. He worked as a teacher and preacher at the London Missionary Society. Later, he found an opportunity to go to Nanjing and join the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. He was even appointed by the Heavenly King Hong Xiuquan as the “Gan King”, responsible for implementing reforms. He wrote a book called A New Treatise on Political Counsel, detailing his reform ideas, including law, education, news, etc., which were mostly inspired by the British system during his stay in Hong Kong.

It is said that Hong Rengan and James Legge got along very well; they used to stroll arm in arm, being each other’s bosom friends.

Hong was the second Chinese close friend of Legge, after Ho Tsun-shin.

Legge admired Hong Rengan very much and had high hopes for him becoming an excellent Christian. Unfortunately, when he went back to England for a vacation, Hong ran away.

In 1861, Legge unexpectedly received a letter from Hong Rengan from Nanjing, proposing to purchase two sets of large and small movable type and a printing press.

But this deal didn’t come to fruition, did it?

How could it not?

The historical records don’t mention it.

Just because it is not recorded in history does not mean it didn’t happen.

How do you know –

Of course we know, because we are the protagonists.

Miss Talented, please be patient. Let’s talk about this later.

Let’s continue talking about the buyers of Hong Kong Type.

Other Chinese buyers include Shanghai District Official Ding Richang, and the Office of Foreign Affairs in Beijing, which was the Foreign Ministry established by the Manchu Qing government in response to the new international situation.

We even exported far overseas! The Royal Printing House of the French Academy was the first to purchase a batch, and then the Russian government also placed an order. In 1858, Professor Hoffmann, the translation officer of the Dutch Ministry of Colonies, bought a set of small movable type from Anglo-Chinese College and handed it over to Tetterode Foundry in Amsterdam for storage and use.

This batch is the Hong Kong Type we just found back in the Netherlands! I’ve seen them with my own eyes!

After more than a century and a half, we finally see the light of day again!

This is the connection we have with you.

Forgot to mention, there was an American, William Gamble, who, on his way to the Chinese and American Sacred Classic Book Establishment in Ningbo in 1858, passed through Hong Kong and visited Anglo-Chinese College. Later, he wrote a letter to order a set of movable type from Legge, but only bought one piece of each character. It is not difficult to see that he intended to recast the movable types into matrices for his own mass production.

Indeed, after the Chinese and American Sacred Classic Book Establishment was moved from Ningbo to Shanghai and reorganized into the American Presbyterian Mission Press, Gamble used the newly invented electroplating method to remold all the Hong Kong typefaces into copper matrices, then used the copper matrices to recast them into lead type. These two sets of lead type were not only used for their own printing purposes, but also sold as their own product.

Gamble, who was exceptionally brilliant in technological innovation and business acumen, collected Chinese movable type of various sizes and quality from multiple channels. In addition to two sets of Hong Kong type, there were also Berlin and Paris type, both of which were composite movable type created by Europeans. Together with two kinds of smaller type supervised and produced by himself, Gamble had in possession a total of six sizes of Chinese movable type. The American Presbyterian Mission Press in Shanghai became the most well-equipped type supplier at that time.

Gamble numbered the type based on their sizes, which was the first time Chinese movable type was systematized. Number one was the large Hong Kong Type, number two was the Berlin Type, number three was the Paris Type, number four was the small Hong Kong Type, and numbers five and six were self-made Shanghai Type.

In December 1868, the China Church News published an advertisement for the sale of six sets of type from the American Presbyterian Mission Press. Since then, the type business of the Anglo-Chinese College took a hit and declined.

However, from our perspective, there is no real cause for regret.

Our descendants have been scattered all over the world.

After Gamble left the American Presbyterian Mission Press, he was invited by the emerging Japanese industrialist Shozo Motoki to teach Chinese movable type printing in Nagasaki. It was the early Meiji Restoration period, and Japan was eager to become a modern country and actively learn Western technology. Gamble’s trip initiated the modern printing industry in Japan.

The printing workshop of Shozo Motoki replicated the movable type of the American Presbyterian Mission Press by electroplating, which later became the commonly used Ming font in Japan. According to the six types of movable type Gamble had created, they were compiled into numbers one to five and number seven, with the addition of the initial number and number six. This developed the future method of noting font size. The Ming font numbers one and four originated from the Hong Kong font.

Our figure appears in Japan.

Hong Kong Type is also a world type.

Since Morrison began trying Chinese printing and advocating the casting of Chinese movable type, it has been over sixty years. The first set of Chinese lead type was not only successfully completed but also widely disseminated. The efforts of the London Society missionaries in this regard had finally come to an end.

We have to be independent of our fathers.

We will evolve into a new generation of Chinese movable type.

But our roots are always in Hong Kong.

No matter where we go or what we become, we are always the Hong Kong Type.

But what about James Legge’s Chinese Classics? He was still continuing to translate, wasn’t he?

Of course, we have to talk about him.

But we should also talk about Wang Tao.

The combination of Wang Tao and James Legge.

Moving from the East to the West, and from the West to the East.

It’s not about domination, but integration.

It’s not the principle of fatherhood, but of motherhood.

That is our source.

And you, Miss Talented, that’s the homeland of your soul.

* The Chinese title of Chinese Serial is 遐邇貫珍, which means literally “Valuable News from Far and Near”.