I would like to know, as spirits, do you come from heaven?

What does it mean to come from heaven?

Are you created by God, or born of nature? Are you spirits of God, or spirits of nature?

Is there a distinction between God and Heaven?

Or neither?

You always want to make distinctions.

Without distinction, I can’t understand.

There’s a kind of understanding that involves distinction, and another kind that doesn’t require distinctions.

Are you suggesting the former involves the body or material, and the latter is tied to the soul or spirit?

No, the former distinguishes between body and soul, material and spiritual, while the latter makes no such distinctions.

Body and mind are one, Miss Talented.

We are both material and spirit.

We are lead, the ink that prints the characters, the form of the characters, and what the form represents.

The character spirit is both one and many, many and one.

Your body is your spirit.

The story of your soul is the story of your physical and spiritual unity.

The Word became flesh, the Father and the Son, Holy Spirit and material, two in one.

God and Heaven, aren’t they two sides of the divine and nature?"

The most controversial aspect of James Legge is his attempt to find the Christian God in ancient Chinese beliefs.

In the ancient texts before Confucius, he saw the existence of the supreme Creator “Shang Di” (the Highest Emperor). This proves that Eastern and Western beliefs share the same origin, and there is a universal God. The Chinese knew about the true Creator long ago, but the pure original faith has been gradually forgotten.

This is also why he was dissatisfied with Confucius and Confucianism.

Did he not respect Confucius?

Yes, he respected Confucius as a moral educator.

He especially valued Confucius’s golden rule of “Do not do to others what you do not want done to yourself”. However, compared to Jesus’s “Love your enemy as you love yourself”, Confucius’s benevolence is just a negative version and of a lower rank.

However, concerning declarations such as “Worship God as if God is here”, “the Master does not talk about strange forces or chaotic spirits”, and “If we do not know about life, how can we know about death”, he thought that these were significant shortcomings of Confucius.

Confucius either ignored or evaded the “Shang Di” that the ancient saints worshipped.

From the perspective of Christian monotheism, Legge values the faith of worshiping the heaven and the highest god before the Zhou Dynasty. Confucius’s ambiguous attitude towards spirits and gods is not a progress, but a regression.

From the philosophical perspective, Confucius lacks enthusiasm for metaphysical ultimate, and only cares about the order of the human world.

Legge concluded, “I hope I have not done him injustice; but after long study of his character and opinions, I am unable to regard him as a great man. He was not before his age, though he was above the mass of the officers and scholars of his time. He threw no new light on any of the questions which have a world-wide interest. He gave no impulse to religion. He had no sympathy with progress. His influence has been wonderful, but it will henceforth wane. My opinion is, that the faith of the nation in him will speedily and extensively pass away.”

It sounds like a pretty harsh criticism!

Please note, this is the view from the 1861 first edition of Chinese Classics, which was also Legge’s early view. His evaluation of Confucius would change greatly over the following thirty years.

Wang Tao once said that Legge was the Westerner who understood Confucianism the best in his time.

Wang Tao was kind of a sensationalist, often exaggerating.

But his praise for Legge should be sincere.

Did Wang understand Christianity? Was he a believer himself?

In 1854, when he was hired by the Shanghai missionary station, he was baptized under Medhurst. When he requested to join the church, he wrote a long letter about why he wanted to be baptized.

That letter seemed more like a reform proposal, directly pointing out the mistakes in the strategy of spreading Christianity in China, and then proposing solutions, even recommending himself to write missionary books that could touch Chinese people more.

This is indeed a behavior that is very much in Wang Tao’s style.

So it’s not that he needed Christianity, but that Christianity needed him.

In fact, Wang Tao’s 14-year stay in Shanghai was not a pleasant experience.

He failed the imperial examination and was coldly treated by the court when he submitted a petition. Although he had great ambitions, he was unable to fulfill them and was forced to serve foreigners for a living, engaging in the tedious work of pen and ink. All this deeply humiliated Wang Tao, who had a high opinion of himself.

In desperation, he began to contemplate joining the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom.

In 1862, Wang Tao, under the pseudonym Huang Wan, secretly petitioned the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom on the pros and cons of attacking Shanghai. However, his plans were exposed, and Wang was hunted by the Qing Dynasty. With the assistance of the Shanghai Consul Walter Henry Medhurst and missionaries of the London Society, he escaped to Hong Kong, where he began a life of exile that lasted more than twenty years.

Upon receiving Wang Tao in Hong Kong, James Legge discovered that this man’s scholarship far surpassed all the Chinese scholars he had encountered. He naturally would not miss this rare opportunity and hired Wang as a translation assistant to help him unravel the mysteries of ancient books.

Wang was grateful for Legge’s recognition and kindness. In this time of distress, Legge not only provided him with a place of refuge, but also gave him the chance to display his talent. Applying knowledge for practical purposes was Wang’s lifelong ideal. Even if he couldn’t serve his country for the time being, he could at least promote Chinese culture through Legge.

The former employer of Wang Tao, Medhurst, had long praised his ability in Chinese. The Delegates’ Version of the Bible he helped translate stands out for its elegance and beauty, catering to the reading taste of the Chinese.

However, some critics argue that this version is overly sinicized, misleading people into mistaking Jesus for Confucius and Christianity for Confucianism.

The use of the Chinese character for “benevolence” (仁) to represent the Christian concept of “love” (愛) gives a hint of this.

Translation is not merely about language, but culture.

It is a matter of the soul.

In 1865, Legge published the third volume of Chinese Classics, the Book of Documents.

In March 1867, Legge applied to the London Missionary Society to return to England to reunite with his wife and children, and to devote himself fully to his translation work.

In December 1867, Wang accepted Legge’s invitation to go to England, with his travel expenses and remuneration sponsored by Robert Jardine of Jardine, Matheson and Co. Wang’s rich collection of books was also shipped to England as reference materials.

During his subsequent two-year journey in Europe, Wang Tao broke through barriers, widened his horizons and underwent a profound transformation of his worldview. First-hand experiences and close observations made him put aside his prejudices against foreigners, and truly understand the path to wealth and power in the West.

Wang lived in Dollar, Scotland, with Legge and his family. Besides occasionally going out together, they were fervently engaged in translation work. The two spent day and night discussing and learning together. Wang contributed his profound classical education, while Legge demonstrated his independent thinking and judgement.

During this time, Wang was also invited to give a lecture at Oxford University, with Legge as his translator. In front of the foreign audience, he confidently professed the idea of integrating Eastern and Western cultures, earning warm applause.

In the seclusion of the small cottage in the Dollar countryside, through the seasons, two scholars representing Oriental and Occidental cultures worked diligently, together accomplishing the remarkable feat of bridging two major traditions.

In 1869, the translation of The Book of Poetry and The Ch’un Ts’ew, with The Tso Chuen were largely completed.

In 1870, James Legge returned to Hong Kong to serve as the pastor of Union Church, with a contract term of three years. The main purpose of this trip was to hire the Anglo-Chinese College Printing Office to print volumes four and five of Chinese Classics.

Before Wang Tao left England, he sold his Chinese book collection to the British Museum, totaling 45 works and 421 volumes, for which he received fifty-five pounds.

After returning to Hong Kong, Wang summarized his observations from his European tour, writing the Records of the Franco-Prussian War, where he analyzed in detail the rise of Prussia and its power over France. The work was highly praised for its insightful understanding of the world situation, even Li Hongzhang greatly appreciated it, and its influence even reached as far as Japan.

In 1871, the printing of the fourth volume of Chinese Classics, The Book of Poetry, was completed in two parts.

In 1872, the printing of the fifth volume of Chinese Classics, The Ch’un Ts’ew, with The Tso Chuen, was also completed in two parts.

On March 29, 1873, Legge boarded the French mail ship Le Tigre, leaving Hong Kong for the last time. It was exactly thirty years since he first set foot on this undeveloped island at the age of twenty-seven.

Under the whim of history, James Legge and Wang Tao met, worked closely together, and then parted ways.

After being immersed in Western civilization and totally transformed, Wang Tao, together with Chen Yan and others, formed the fully Chinese-funded Chinese Printing Company. They bought all the equipment and typefaces from the Anglo-Chinese College Printing House for 10,000 Mexican silver dollars, ready to make their mark in the world of Chinese publishing.

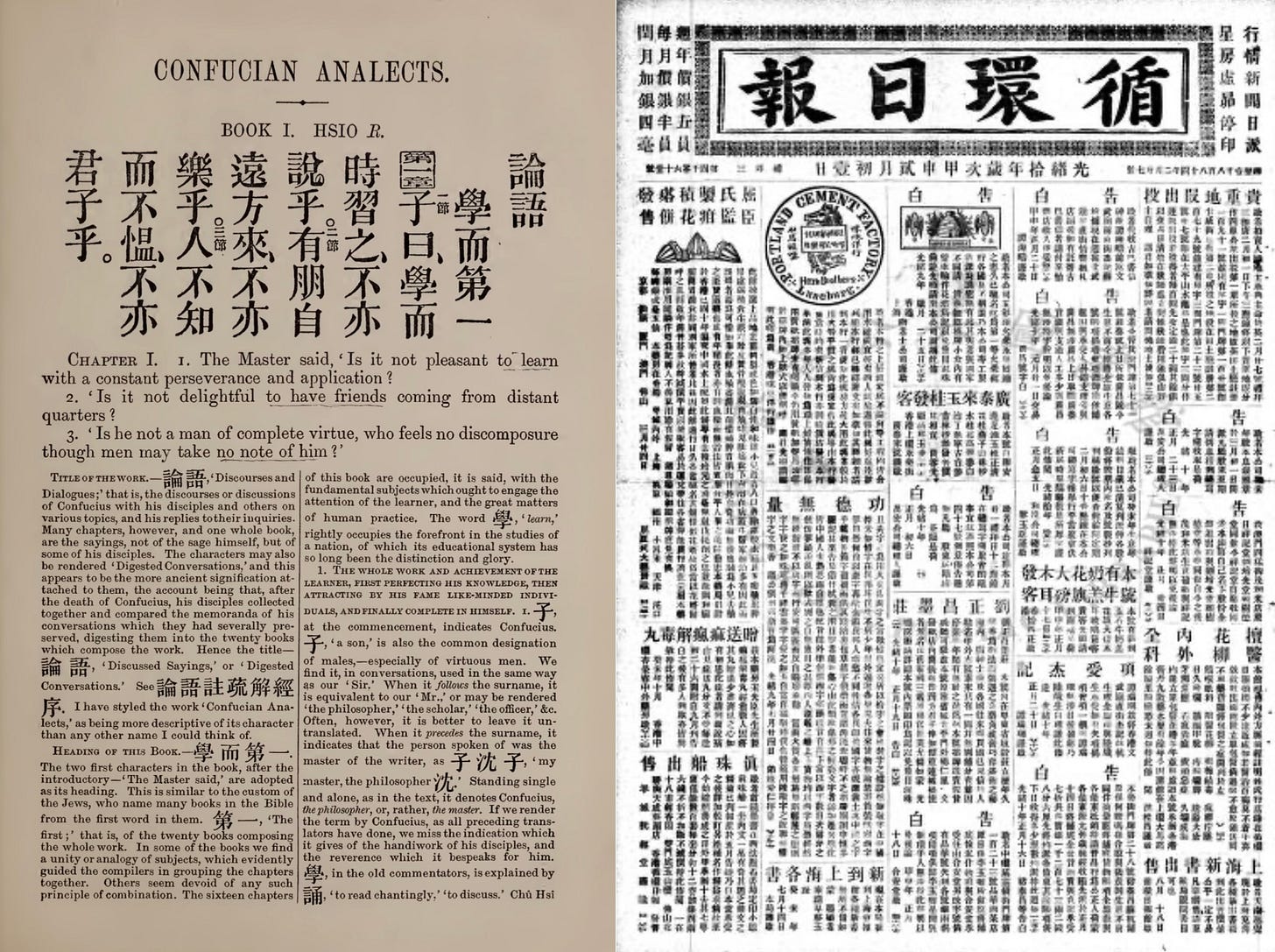

In 1874, Wang Tao founded the Universal Circulating Herald (循環日報), the first editorial newspaper in Chinese and served as the editor-in-chief. He called for reforms in China, becoming one of the earliest forces promoting late-Qing Dynasty reform and self-strengthening movements.

In 1884, the Qing court revoked its warrant for Wang Tao. He retired and returned to his hometown, but that was not the end of his ambition. Within a year, he became the dean of the Shanghai Polytechnic Institution, where he devoted himself to cultivating applied science and technology talent and reforming the Chinese education system.

However, in his later years, he never mentioned his baptism and conversion to Christianity, seeming to want to erase his past service to foreigners.

This suggests that his conversion was insincere.

However, as for Legge’s friendship, it seems Wang would never forget.

Compared to Wang Tao’s distance from Christianity, Legge was getting closer and closer to Confucianism.

At the end of his missionary career, Legge embarked on the most important pilgrimage of his life.

He paid homage to the holy lands of Confucian classics he had studied hard for over thirty years.

He first stayed briefly in Shanghai, then headed north to Tianjin, making his first visit to Beijing.

He visited the Great Wall, the Thirteen Imperial Tombs of the Ming Dynasty, and the Old Summer Palace.

On April 21, he arrived at the “most important religious building in China” - the Temple of Heaven.

With the “mood of a pilgrim”, Legge climbed the circular three-tiered platform of the Temple of Heaven. Standing on its top, he thought of the Chinese people who, represented by the emperor, worshiped Shang Di in the open air on similar altars without idols during the Spring and Autumn Sacrifices over the last four thousand years.

He had always argued that the “Highest Emperor” of the Chinese people is the one true almighty God of Christianity.

Hence, he insisted on translating God as “Shang Di” in the Chinese Bible and debated fiercely with religious sects that favored translating it as “Shen”, causing an irreconcilable rift.

At this moment, on the Temple of Heaven, he firmly believed that his previous arguments were right.

This place was a holy land.

Standing on it, he was deeply moved and fearful, spontaneously took off his shoes, stood barefoot, looked up to worship, and bowed his head to pray. The God of the Heaven is indistinguishable from East to West.

The Heaven of Confucianism and the God of Christianity became one.

Legge’s astonishing actions at the Temple of Heaven provoked the dissatisfaction of conservative missionaries, who criticized him for blasphemy against Christianity and even accused him of heresy.

The old hatreds and new enemies born from the translation controversy would continue to ferment in the remaining years of Legge’s life.

The pilgrim continued his journey, riding on a bumpy mule-drawn carriage, staying in simple inns, eating simple food, appearing travel-worn. He successively ascended Mount Tai and visited the Confucian holy places such as Qufu Confucian Temple, Confucian Forest, Confucius’ Tomb, and the former residence of Mencius.

Legge fulfilled his wish, bid farewell to China, and returned to the UK via Japan and the United States in the same year in August.

Compared with Morrison, Milne, Dyer, and even Medhurst, Legge’s missionary career can be said to have ended perfectly.

However, his story has not yet finished.

After resigning from his missionary work, James Legge was finally able to engage in scholarly work legitimately. Under the advocacy of the Orientalist scholar Max Müller, the University of Oxford established the position of Chinese Professor in 1875. Legge, with his accomplishment of translating five volumes of Chinese Classics, was universally recognized as a world-class sinologist and was invited to take on this new position, which was regarded as a truly deserved honor.

Even at the age of sixty, he could still embark on a new career. Legge deeply believed that it was God’s grace.

Although his Chinese classes at the university were not warmly received and the number of students were few, he did not slacken in academic research for a moment.

He persistently maintained the reading habits he developed in his youth, waking up at three in the morning, reading by lamp until dawn.

The light that illuminated the Chinese classics has changed from candles or oil lamps to gas lamps, and the pen used for translating Chinese classics has also changed from quill to fountain pen.

In the subsequent two decades, James Legge completed the translations of The Hsiao King (Classic of Filial Piety), The Yi King (Book of Changes), The Li Ki (Book of Rites), The Tao Teh King, The Writings of Kwang Tse, and others, which were published in the "Sacred Books of the East" series edited by Max Müller.

Although not entirely perfect, it was already a remarkable milestone.

Being free from his missionary status, he voiced his opinions and discussed matters from a scholar’s perspective without any reservations.

He daringly compared Christianity and Confucianism on equal footing, concluding that Confucianism includes the worship of God. Although he still believed that Christianity ultimately surpasses Confucianism, he acknowledged that there are many aspects of Confucianism worth learning for Christians.

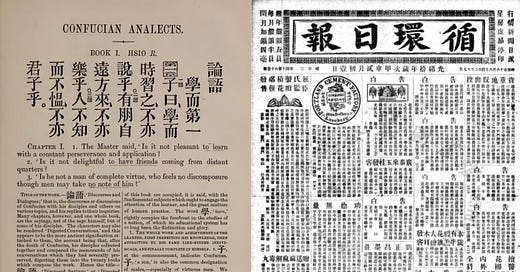

In 1893, the first volume of Chinese Classics, including Confucian Analects, The Great Learning, and The Doctrine of the Mean, was republished by Oxford University Press in the United Kingdom. In the foreword, James Legge revised his view of Confucius thirty years ago.

“I hope I have not done him injustice; the more I have studied his character and opinions, the more highly have I come to regard him. He was a very great man, and his influence has been on the whole a great benefit to the Chinese, while his teachings suggest important lessons to ourselves who profess to belong to the school of Christ.”

The two conclusions are poles apart!

His sympathy, even admiration, for Confucianism, his insufficient insistence on the absolute superiority of Christianity, and his dedication to secular academic pursuits and adoption of the methods of comparative religious studies, are all reasons for the fierce attacks Legge faced from religious conservatives in his later years.

They collectively referred to these tendencies of religious concession as "Leggism".

In the face of malicious criticism, Legge maintained a balanced and composed attitude, neither humble nor aggressive.

He truly became a Confucian scholar.

James Legge and Wang Tao, old friends and colleagues, passed away one after the other in 1897, the former at the age of 82 and the latter 69.

Legge’s second wife, Hannah, passed away eight years after he returned to England. Among their eleven children, five died young. He had fifteen grandchildren in total.

From Robert Morrison’s determination to destroy Eastern deities and Bodhisattvas, and to rescue the people of China from the poison of idol worship, to Legge’s admiration for Chinese culture, being convinced by the wisdom of Confucianism and Taoism and dedicating himself to the translation and interpretation of Oriental texts for his whole life, nearly a century passed.

The God of the West and the Spirit of the East contested in the field of written words, with no decisive victory.

Overcoming Chinese characters, and being overcome by Chinese characters, is hard to differentiate and explain.

From competing to cooperating, the Hong Kong Type is a crystallization, and the Chinese Classics is an achievement.

The story of the Hong Kong Type is finally coming to an end.

No, Miss Talented, the story is not over yet.

What else follows?

There are still stories about your ancestors.

My ancestors?

Haven’t you been searching for the roots of your soul?

Is this what ancestors mean?

In 1853, a teenager with the surname Dai and a given name of Fuk, joined the class at Anglo-Chinese College, where Legge was teaching.

In 1856, the free boarding school closed, and the teenager stayed as an apprentice in the printing workshop.

In 1861, the young printer Dai Fuk participated in the printing of Chinese Classics.

In 1873, Dai Fuk and other employees of the printing office, joined the Chinese Printing Company together.

In the same year, Dai Fuk adopted a newborn orphan and named him Dai Dak.

My great-grandfather Dai Dak?

Exactly.

Who was Dai Dak’s mother?

Dai Dak’s mother was called Lai Heng Yi.

Why did Lai Heng Yi abandon her newborn son?

It’s a long story.

What’s her relationship with Dai Fuk?

Do you really want to know?

You popped up on my screen, rattling on and on, isn’t it just to tell me about this?

Indeed.

Then please, go on!

It’s better for us not to say it.

Who should say it then?

Let Dai Fuk himself say it.

What did Dai Fuk say?

He has written a book called Six Records of a Resurrected Life.

Where can I see this book?

It is no longer available. However, you can rewrite it.

Me, write?

As in a seance.

Whose spirit will I connect with?

Dai Fuk’s spirit.

Can I communicate with Dai Fuk?

Yes. Are you ready?

I can bear anything.

You should rest first. When the time is right, the spirit of Dai Fuk will come to you.

How about you?

We have already completed our mission.

We have told you everything about the origin of the Hong Kong Type.

You are the one we chose, as our inheritor.

Only one link is missing, Dai Fuk’s link, and we are connected in a line.

Merged as one.

Thank you for your patience over the past few months.

We, the character spirits, express our gratitude to you.

Goodbye!

We will live forever in your heart.

And become the guardian of your soul.

Please remember the secret signs we have agreed on.

The characters are spirited, and the people are talented.

The people are talented, and the characters are spirited.

They are the same.

Characters are made by people.

People are born from characters.

Characters are people.

People are characters.