活 (Alive)

Later on, printing appeared.

You have come.

Miss Talented, characters always keep their promise.

I thought it was a dream.

Calling it a dream is not wrong.

But I'm clearly awake.

Being awake is also a kind of dream.

You mean a lucid dream?

No, we are not talking about the kind of dream that can be controlled by conscious awareness. We are saying that consciousness itself is a kind of dream.

Consciousness is a dream... strange... I do have this feeling.

No need to find it strange; this is a good phenomenon.

Is this good? I feel a bit scared, like I can't tell what’s real and what’s not.

You've been reading lately, haven’t you?

You know everything?

We are character spirits, we know everything about words.

There’s nothing unrelated to words, so we can say we know everything.

I’ve been reading about the history of printing, but I’m reading slowly.

That’s fine; let’s talk about the history of printing. Do you know the origin of printing?

Every schoolchild knows that it’s one of China's four great inventions.

Good. What about the time?

The Tang dynasty, around the 8th or 9th century AD.

The so-called invention, from nothing to something, what’s the key?

Is it intelligence?

You mean to say that the Chinese are more intelligent?

That’s not what I meant.

Intelligence has no direct connection to invention.

So, more importantly, it is...

A shift in consciousness.

Your terms are very modern.

It’s just keeping up with the times. If you like, in old language, it’s a divine transformation.

I don’t quite understand.

Understanding how to reverse the characters, carve the reverse, and print the correct text, that’s not about intelligence. People used to know nothing about it, and then suddenly they knew. Once they knew, they didn’t find it strange at all. What was strange was why they didn’t know such a simple truth before.

It’s like the moment when a child discovers that the image in the mirror is its reflection.

Is that a kind of growth?

The term “growth” is too Western. We used to say — dream awakening.

So it’s an awakening.

To be awakened is also too Western. Dream awakening means you know there are dreams, you know there is waking, and you know that dreaming and waking are different, but you don't know if you’re in a dream or waking. There are dreams within waking, and waking within dreams. It's like positive and negative, yin and yang; there's no order or hierarchy.

Like me now?

Look! She truly is a talented person!

Her intuition is good.

Where have you gone off to again?

Let’s get back on track. A shift in consciousness is a divine transformation, so printing is divine magic, and the printing press is a divine artifact. This is the main premise.

Does this have to do with the fact that the first printed material was Buddhist sutras?

Exactly right. Buddhist sutras are sacred texts, and only later were worldly books printed. In China, paper and words had always been sacred, especially printed ones. That’s why there used to be the custom of venerating paper.

Paper with written or printed words couldn’t be discarded or trampled on; it had to be collected together and burned.

Facilities for burning paper with words were called “Towers of Venerating Words” or “Pavilions of Venerating Words.” In the past, there was also a place in Kowloon Walled City for venerating paper with words, built by Qing Dynasty officials.

Really? I've never been there. This habit is also quite eco-friendly.

Thou art exceedingly silly; those are two completely different concepts. Environmental protection lacks soul; paper with words has it.

You’ve gone off track! Let's talk about movable type. Wasn’t movable type also invented by the Chinese?

Yes, the earliest record is of Bi Sheng in the Song Dynasty. Although there’s no physical evidence, what Shen Kuo said in Essays of the Dreamy Stream should be credible.

Since it’s Chinese stuff, why do you Western-style movable type make such a fuss, as if you are the only authentic movable type?

You’re not wrong; although we are Chinese characters, being movable type, we are Western-style, so our identity is a bit awkward.

There’s nothing awkward about it; since there’s no distinction between dream and waking, yin and yang, there's naturally no distinction between East and West. This is where the spirit of characters resides.

You have disagreements. How interesting!

We are one and many, many and one. From the perspective of many, of course, we can have different opinions.

You sure are a talkative bunch! I still don't understand, since China already had movable type, why wait for the West to introduce movable type printing?

It’s simple, movable type was never widespread in China. It was sporadically made, but the practice wasn’t inherited or disseminated. Even the copper movable type used to print the Complete Collection of the Books of Past and Present during the Kangxi era of the Qing Dynasty, or the Hall of Martial Valor Deluxe Version wooden movable type created during the Qianlong era, though grand in scale and numerous in number, were not cast but carved individually. They were later decayed, discarded, or melted down for copper coins. This way of making movable type was doomed to failure.

It is said that the most common movable type in China was used to print genealogies. It was carried by the engraver from village to village, but it was wooden, incomplete, and not durable.

What’s different about Western movable type? Why is it so impressive?

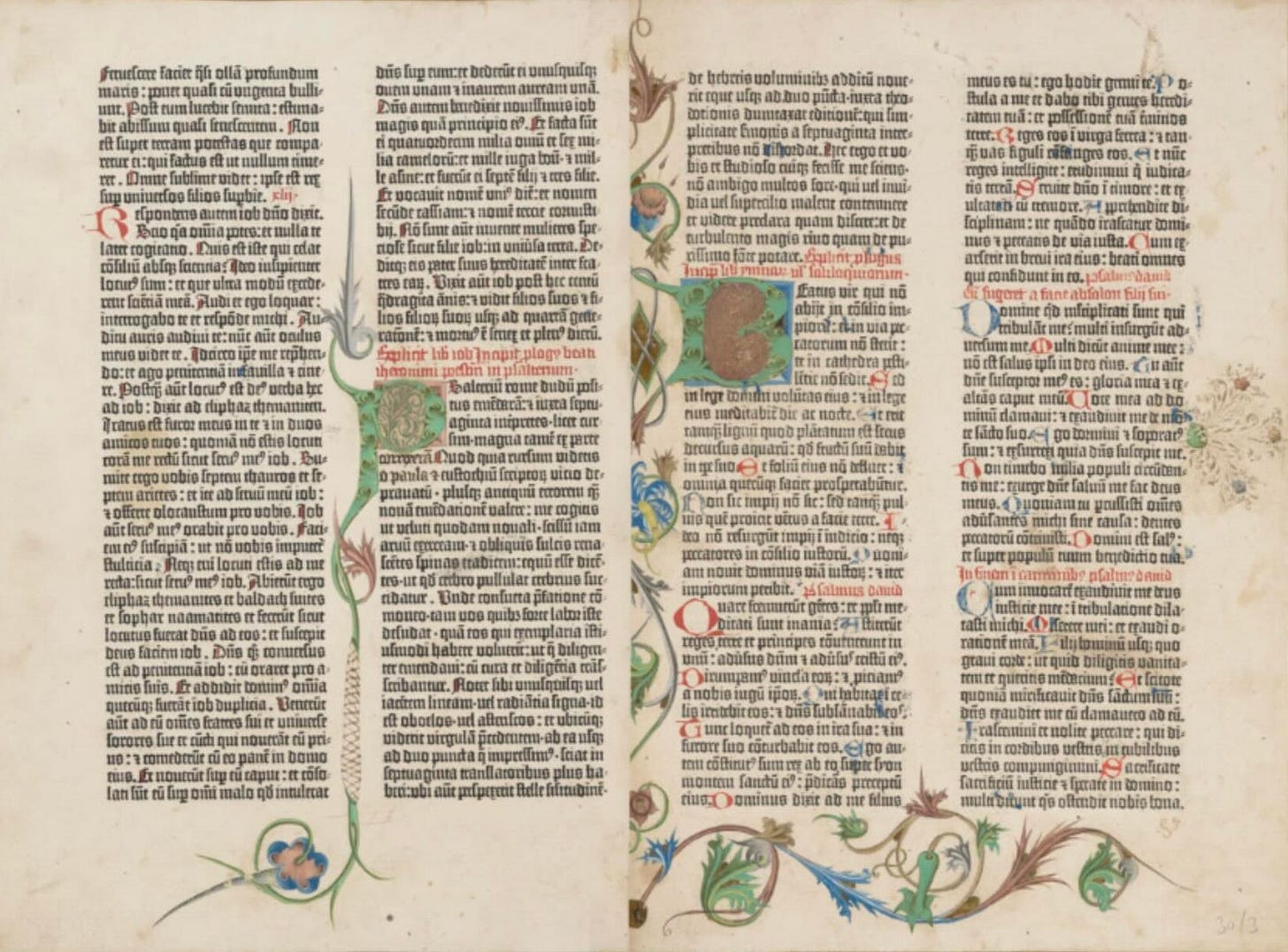

Originally, the West was far behind. In the Middle Ages, Europe was still shrouded by darkness and backward in culture, totally unable to compare with the Tang, Song, or Ming Dynasties. However, in the 15th century, around the beginning of the Ming Dynasty, a craftsman in Germany named Gutenberg invented the method of casting movable type.

Some also say Gutenberg was a noble because his family was involved in metallurgy, and coin casting was connected to royal power. In the German city-states of that time, the definition of nobility was loose, so it could also mean a traditional local magnate. Although little is known about Gutenberg’s life, there is no doubt that the art of movable type printing began with him.

So, what is the so-called Western-style movable type? How does it work?

The exact method of Gutenberg is no longer known, but soon after, the procedure for making movable type was established: first, the image of a letter is carved on steel and made into a punch, then the punch is pressed onto a copper plate to create a matrix, and finally, the lead type is cast using the matrix. With punches and matrices, movable type can be reproduced endlessly.

Moreover, with movable type, typesetting can be done. After printing, the type can be taken apart and reused. There’s no need to re-carve the plate every time, saving both time and money. Additionally, with machine printing, the efficiency is hundreds or even thousands of times higher than traditional engraving.

It’s indeed very clever. But listening to it now, it doesn’t seem like something that’s hard to understand!

We’ve said the key is the divine transformation! It's a shift in consciousness!

Concave and convex complement each other, yin and yang balance. Endless regeneration, continuous circulation.

The thing itself isn't difficult; anyone of ordinary intelligence would understand. But why couldn’t people think of it before? The first person to think of it, and also accomplish it, is a person who has achieved dream awakening.

He’s a divine being!

He’s a devil!

Gutenberg, using the method he had invented, first printed the Latin Bible. The text of this Bible was exquisitely crafted, flawless, precise, and identical, reaching a level of perfection that was incomprehensible to people of the time.

The Bible of that time was originally hand-written by professional scribes on parchment. No matter how skilled the calligraphy, there would always be human imperfections and mistakes. However, people believed that hand-copied books were blessed by the Holy Spirit, and copying them became a sacred ritual.

In contrast, Gutenberg’s technology eliminated human involvement, relying entirely on mechanical processes. In just an instant, it could print completely identical, good-looking, and error-free content, and it could be mass-produced.

Such a method was not only contrary to divine guidance but was even considered a heretical art.

I think it’s a bit like the miracle of the loaves and fishes.

Yes, as long as we complete the shift in consciousness, we'll know that metal and machinery are one with God, and movable type has a spirit.

Movable type, since it moves, has life in it.

Well said!

Applause!

Clap! Clap! Clap!

Sorry, we don’t have hands, so we can only use onomatopoeic words.

Hahaha! You character spirits are really cute!

Miss Talented is laughing!

This is a good sign.

So, shall we end here for today?

Let’s talk a little more.

Hey, don’t talk among yourselves as if I’m not here!

Not at all! We’re about to get to the key point — the missionaries coming to the East.

Let’s go back a little bit. What changes did Gutenberg’s magic bring?

It was not just about making the printing of the Bible more convenient. After the technology became widespread, people began to print other books, and more and more of them. Philosophy, science, humanities, literature, everything was printed; it was like an explosion in knowledge.

People became enlightened, the age of the divine came to an end, the Renaissance began, Humanism arose, and atheistic heroes proclaimed God is dead.

It changed all of Europe, even all of humanity. Saying that it was the printing press that achieved this is not an exaggeration.

The power of movable type is comparable to the fruit of the tree of wisdom in the Garden of Eden.

This artifact, wasn’t it used to oppose God?

It’s not entirely like that. Martin Luther’s “Ninety-Five Theses,” written to protest about the selling of indulgences, were widely disseminated through movable type printing, sparking the Reformation.

Protestantism and movable type printing actually went hand in hand, didn’t they?

Some say Protestantism is the cornerstone of capitalism. Roman Catholicism was based on the medieval feudal society of nobility, while Protestantism was grounded in the Industrial Revolution, urban modernization, and the rise of the middle class.

But the nineteenth century was also a time of European imperialistic colonial expansion.

In political system, industry, commerce, trade, science, navigation, and military might, Britain was at the world’s forefront, and it also produced the first wave of Protestant missionaries coming East.

But this doesn’t mean that the missionaries were supported or sent by the state. Far from it; initially, they even faced official disdain or obstruction, out of fear that they would anger the Qing court and hinder trade with China.

The London Missionary Society, composed of several independent denominations outside the national church, represented unofficial, spontaneous civic power. Non-Anglican factions did not support imperialism and opposed the opium trade and military expansion.

That said, it cannot be denied that the missionaries indeed followed in the footsteps of the Empire, coming along the paths opened by it. This situation continually posed a dilemma for some missionaries.

The Kingdom of God also relies on earthly power to expand.

That is God’s mysterious arrangement, something humans cannot fully understand. They explained.

So the missionaries came.

Yes, but their divine artifact didn’t seem to be immediately useful.

Because of the language barrier.

It’s the writing.

Chinese characters are the most tenacious and formidable in the world.

These characters, unchanged in the land of China for a thousand years, consistent through the ages, and used all around the country, even if subjected to foreign invasions or influenced by different religions, can absorb and assimilate them, making them part of itself.

Those who cannot control this powerful spirit will be consumed by it.

These characters are incredibly complex, inspiring awe in those who look upon them.

Westerners once thought that even if they lived ten lifetimes, they would never be able to learn Chinese.

But someone was not afraid.

Who was so bold?

This person was named Robert Morrison.

[To be continued]