Six Records of a Resurrected Life

III. Uprising

Heng Yi, ever since the time when you rejected me, I might not have lost heart, but I also did not dare to force you. Moreover, you were still young, and I was just starting my own way in the world. Thinking that we still had a long way to go, I put this matter aside for the time being. But truth be told, my heart was also wounded by you. I thought you rejected me as a mere apprentice, using your father’s disapproval as an excuse to make me give up. After all, the daughter of the owner of the western-style photo studio, no matter how I saw it, was above me. To win your heart and your father’s approval, I had to make a career for myself. Thus, I set my mind to strive upwards, and open my own printing workshop in the future. But I didn’t want you to think that I was just moody, insincere, or lacking in resolve, ready to retreat at minor obstacles. Therefore, I would often drop off some small Bible booklets in the mailbox when I passed by the photo studio, hoping that you would read them carefully in your leisure time, and know that I wasn’t all talk, but truly meant what I said. One of them was the sermon on the mount where Jesus tells his disciples about the eight Beatitudes. I took the time out of my busy schedule to print it myself, hoping to tell you that the meek who have been humiliated in this world will find comfort in the kingdom of heaven, which is a great blessing. I’ve recorded it as follows for you to review.

When Jesus saw the crowd, he went up the mountain and sat down. When his disciples gathered around him, he began to teach them, saying, “Blessed are the humble, for the kingdom of heaven belongs to them. Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted. Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth. Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled. Blessed are the merciful, for they will receive mercy. Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God. Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called the children of God. Blessed are those who are persecuted because of righteousness, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are you when people insult you and persecute you, and falsely say all kinds of evil against you because of me. Rejoice and be glad, because great is your reward in heaven, for in the same way they persecuted the prophets who were before you. You are the salt of the earth. But if the salt loses its saltiness, how can it be made salty again? It’s no longer good for anything, except to be thrown out and trampled underfoot. You are the light of the world. A city built on a hill cannot be hidden. Neither do people light a lamp and put it under a bowl. Instead, they put it on its stand, and it gives light to everyone in the house. In the same way, let your light shine before others, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your Father in heaven.”

By the end of the tenth year of Xianfeng, Mr. Wong Shing received a letter from Hong Rengan. At that time, Big Brother Hong had already become the King Gan of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. The purpose of his letter was to place an order with Anglo-Chinese College for a pair of large and small typefaces and a printing press. Upon hearing this news, the missionary station was overrun with excitement, as this move was seen as a significant contribution to the construction of the Heavenly Kingdom and the spread of the Gospel of Christ. Mr. Legge commented, “While others provide guns and ammunition to rebels, I’m glad to supply them with other things.” Mr. Legge had a deep friendship with Big Brother Hong and was pleased to see him managing the country through civil means and promoting religion. Previously, Mr. Joseph Edkins, a colleague from the Shanghai station, had visited the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom several times, meeting face to face with the King Gan and the Loyal King. After returning to Shanghai, he wrote articles for the North China Herald, detailing the scale, policies, and daily life of the Heavenly Kingdom. Although there were deviations and errors in their practice of doctrine, they were not deemed heretical and it was hoped that the mistakes could be corrected gradually.

After the successful printing of the first and second volumes of Chinese Classics, the printing house fully devoted itself to typecasting to meet the needs of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. In the same year in October, Mr. Wang Tao came from Shanghai. When the missionaries visited Suzhou earlier, Mr. Lan Qing also accompanied them. Later, he wrote to the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom under a pseudonym, offering strategies for attacking Shanghai. His letter was intercepted by the Qing army, who subsequently issued an order for his arrest. Mr. Wang hid in the British consulate in Shanghai for four months, eventually sneaking out of the country and heading south to our port. Mr. Wang Lanqing is a native of Puli, Jiangsu. He had been working at the Shanghai missionary station for over ten years, serving as the Chinese assistant to the late Mr. Walter Medhurst. Many of chapters of the Delegated Bible that we have read were revised by Mr. Wang, with elegant and fluent phrases. In the past, the elder Mr. Wat Ong had a temporary stay at the Shanghai station, where he got to know Mr. Lan Qing. Now as he was stranded in Hong Kong, Mr. Wat generously helped him, providing him with glasses, clothing, and meals at the tea house. Because Mr. Wang was not familiar with the local dialect, Mr. Wat acted as an interpreter and introduced him to Mr. Legge. Impressed by his talents and learning, Mr. Legge hired him as a Chinese teacher to assist with translating Chinese Classics. Mr. Lan Qing also visited our printing house. The movable type used by the London Missionary Society Press in Shanghai originated from our printing house. Now that he had seen the genuine prototypes, he was full of admiration.

When Mr. Wang Tao first arrived in Hong Kong, he looked weary and lost, like a homeless dog, which startled those who saw him. Moreover, he struggled with the language barrier, was unaccustomed to the food, and was financially embarrassed. Except for two or three acquaintances who accompanied him, he was extremely bored and lonely. One day, as I was on my way to the market, I saw Mr. Wang alone in a roadside tavern. I bowed my head in acknowledgement, not wanting to disturb him. Surprisingly, he called me over and whispered something in Shanghai dialect. I did not understand, so he tried to express himself through gestures, implying that he might not have any money. So, I reached into my pocket and paid for his drink. He thanked me profusely with deep gratitude. I kept saying that it was nothing and he didn’t need to thank me. Then he invited me to sit down and poured me a drink to express his thanks. Normally I seldom drink, but rejecting him would be disrespectful, so I forced myself to drink it down. Mr. Wang was quite talkative. Even if we barely understood each other, he still spoke enthusiastically and endlessly. After finishing a drink, he ordered another. Half an hour passed, and he was visibly drunk. He leaned on me and whispered in my ear again, I guessed the meaning could be, whether or not I knew where to find a girl. I neither knew the place nor dared to refuse him, so I played dumb and pretended not to understand. After several attempts, he gave up, probably cursing inwardly at my stupidity.

A month later, around the time of Winter Solstice, I had just gotten off work one evening when I saw Mr. Wang Tao coming out of the missionary building. He immediately strode over to me, and said, “Little Fuk, come, let me buy you a drink.” We walked out of the gate together, and he took me towards Sheung Wan, discussing various topics enthusiastically along the way. Eventually, we arrived at a neighborhood filled with brothels. At this point, I understood his intentions - he wanted to repay a favor from the time we had drinks together. I hurriedly declined, pretending I had something urgent to attend to, and therefore couldn’t accompany him. Mr. Wang looked disappointed, but he let me go without insisting, and went off on his own into the nightlife. As I hurriedly walked away and turned a corner, I saw you coming towards me, accompanied by an older woman. I was taken aback and hid to the side. I saw you, dressed in traditional Chinese clothing, disappearing into the night, your beauty shrouded in an alluring mystery, as you walked elegantly into a small building. I quietly followed and peeked into the building from outside, but it seemed just like an ordinary residential house, with nothing out of the ordinary. Shortly afterwards, I heard the sound of a pipa tuning from upstairs. After a while, a song was played, though it sounded a bit like beginner’s work, stopping after several sections, then starting over again. This went back and forth several times. I figured that you were probably here just to learn music. I stood there for a while in the dead of the night, gradually feeling the cold, and regretfully having to part with the sound of the pipa. I marked down this location, intending to come back another day. However, several attempts proved fruitless. The scene I saw that night seemed elusive and unreal, yet it was inappropriate to inquire. This left me with a sense of bewilderment.

One night, I bumped into Ah Wong. Noticing his coarse cotton clothes, he told me he had become a dock worker. Consequently, I joined him for dinner at a teahouse, where I found out that he had left the gang, and yet was reluctant to return home. Instead, he was making a living doing odd jobs around the city. He pulled out a newspaper from his pocket, which listed the price of goods from Hong Kong, and pointed to a column about passenger ships, proclaiming his plan to try his luck at gold mining in San Francisco. I was surprised and worried after hearing this. There had been issues with human trafficking and forced labor, which had drawn the condemnation of newspaper editorials for this evil practice. Furthermore, scandals of discrimination against Chinese workers had erupted in San Francisco. To make matters worse, there were frequent reports of shipwrecks due to poor management. But Ah Wang had a penchant for adventure, and I knew it would be useless to dissuade him, so I could only advise him to take care. It was with a feeling of nostalgia that I recalled our childhood antics, which seemed like a different lifetime. After our meal, our past differences were put aside, and we encouraged each other before parting ways.

At that time, the characters ordered by King Gan had already been cast, and only awaited the arrangement for payment and delivery. However, the situation between the Heavenly Kingdom and the Qing court was drastically different from the previous years. Although it was said that the major Qing camps, both south and north of the Yangtze River, had been annihilated by the Heavenly Army, the Xian (Hunan) Army led by Zeng Guofan had taken Anqing, leaving no defensible positions upstream of the Heavenly Capital. Also, the Heavenly Army’s attack on Shanghai had failed, repelled by the Foreign Rifles Squad (aka the Ever Victorious Army) formed by Westerners. British and French forces, allied with Li Hongzhang’s Huai Army, aimed to attack Suzhou. Thus, the Heavenly Capital was essentially facing enemies from both sides, making the situation extremely precarious. At this juncture, it was not easy to enter the Heavenly Capital from Shanghai. Mr. Legge was very dissatisfied with Britain’s intervention in the Chinese civil war and their support for the Qing court, and he publicly opposed it through letters to newspapers. However, most missionaries had lost faith in the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom and no longer defended it, leaving it to its fate. To Mr. Legge, casting type for King Gan was not just a matter of business, but of moral principle. Yet, since Mr. Wong Shing should not supervise the task personally, the candidate to oversee the delivery was undecided. Remembering the righteous spirit of Brother Hong, and his heart-stirring proclamations, who would want to live a life of humility and servitude, like ants? As a result, I volunteered to deliver the movable type to King Gan. After much discussion, Mr. Legge and Mr. Wong agreed, but they instructed me to wait in Shanghai and not to act impulsively. A steamship named the Amos was then selected to transport two sets of movable type and a personnel member, and it would set off soon. The ordered printing press had already been directly shipped to Shanghai from Britain.

About this business trip, I thought back and forth, unsure whether I should tell you or not. But considering we had no dealings with each other, I feared that it would be sudden and laughable if I came to say goodbye. As for writing a letter to you, I wouldn’t know where to start. After hesitating for quite a while, I had no way to express my feelings. On the eve of departure, I returned to the place where we met by chance last time. I wandered back and forth, suddenly hearing the sound of a pipa coming from upstairs again. It was more fluent than before, with a slightly raw tone that somehow enhanced a sense of youthful shyness and pitifulness. After a prolonged prelude, a soft and uncertain singing voice arose, trembling and tentative, like a baby bird’s first cry. The tune was soft, the rhythm slow, full of sorrow. The lyrics were hard to distinguish due to the extended singing style, and I could barely make out the lines, but in the end, it seemed that all the phrases touched my heart. Later, when I looked it up in the lyric book, I recognized that it was this song: “Don’t you dream, for fear that we may meet in the dream and after waking up from the dream, everything will be gone. The word ‘parting’ is surely heartbreaking. You, my dear, you are wandering in the far-off place while your beloved is floating aimlessly on the surface of the water. The longing one is holding a pipa, playing a song, how much desolation lies in the fingertips. If you could let go and not be so heartbroken, you wouldn’t weigh me down so much. Look at me, so skinny, yet still talking about beauty. Today’s love, no matter how good, is of no use. Alas, ten thousand kinds of sorrow, making me shed tears and spit blood out of longing.” After the song was over, I sighed, looked up, and said to you in my heart, “Wait for me to come back.”

Can you stand it?

I can.

Let’s keep going then.

In June of the second year of Tongzhi, or July 1863 by the western calendar, I set off by boat to the north. After six days, I arrived in Shanghai and stayed temporarily at the London Missionary Society’s preaching station, waiting for instructions from Big Brother Hong. At the time, Mr. Joseph Edkins and Mr. Griffith John, who had visited the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, had already left the station. Only Mr. William Muirhead, who had met with King Gan, stayed behind. I asked Mr. Muirhead about the situation and read reports in the North China Herald and British missionary magazines. I also received a copy of A New Treatise on Political Counsel written by King Gan. After reading it in detail, I understood Brother Hong’s advanced views and his great talent and strategy. This publication was actually a letter to the Heavenly King from King Gan, proposing reforms and discussing the way of governance, which is divided into governing by custom, law, and punishment. Of the three, the former is considered superior, as those in power should lead by example. His suggestions like improving transportation, establishing banks, starting companies, issuing insurance, and appointing news officers were all inspired by his observations while living in Hong Kong. He also proposed banning opium, running charities, and appeasing the foreigners, all of which are benevolent policies. If his methods went into effect, the Heavenly Kingdom system would be completely renewed, clearing away the Manchu’s backwardness and conservative ways. However, Mr. Muirhead said that King Gan’s power was in name only and his military defeat last year had led to his demotion. Despite his good intentions, he was powerless to rectify the deviations in the faith of the Heavenly Kingdom. Mr. Mu also believed that King Gan had not fully exerted his efforts, perhaps intimidated by the majesty of the Heavenly King and dared not act rashly, thus he strayed further and further away, making it increasingly difficult to return to the right path. Hearing this, I couldn’t help but sigh.

The London Missionary Society Press in Shanghai used to dominate the letterpress printing industry in North China, having printed millions of scriptures. Its production capacity was truly astonishing, and the power of its rolling press machines impressive. However, nowadays, all was lying idle, the printing industry decaying, and personnel dwindling. The head of the press, Mr. Muirhead, seemed uninterested in maintaining it, hence the current state. As a junior staff, I found this regrettable, but I didn’t dare to interfere. I heard that the American Presbyterian Mission Press managed by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions had risen in recent years and was likely to replace us. Its manager, Mr. Gamble, an American, was a professional printer. When he took over a few years ago, he passed through Hong Kong and visited the Angle-Chinese College, where he purchased a set of lead type of both sizes. Unexpectedly, afterward, Mr. Gamble replicated all our lead type through the newly invented electroplating technique, then openly selling them as his own products. But that’s a later issue, so let’s put it aside for now. As a member of the industry, it’s truly a shame to see the decline of the London Missionary Society Press.

I stayed at the Shanghai missionary station for three months, until mid-September. Suddenly, I received news from King Gan that the payment had been sent to Shanghai by a special messenger and I was instructed to transport the typefaces to Suzhou. The secret arrangements of the canal transportation were overly complicated, which I won’t go into details here. In order to guard against another invasion by the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, the periphery of Shanghai was heavily fortified. Both the Ever Victorious Army and Huai Army were also prepared to launch an attack on Suzhou at any time. The trip to Suzhou was very dangerous, but these two sets of typefaces were valuable, worth nearly four thousand silver dollars. Therefore, I personally took up the responsibility to oversee the transportation and could not delegate it to others. Mr. Muirhead wrote a letter, which served as my proof of identity as a staff member of the missionary station, in case of emergencies.

In early October, I took a small boat upstream along the Huangpu River. As we were flying the British flag, we faced no obstructions during our journey. When we approached the area under the Heavenly Kingdom’s jurisdiction, we transferred to land. We soon arrived at the designated small town, where personnel dispatched by King Gan were waiting. The area had been plagued by continuous conflicts over the past years, leaving fields barren and houses abandoned. Approaching the outskirts of the town, corpses were littered everywhere and the air reeked. The contact who came to meet us was a young man named Ah Leung, a Kwangtung native around twenty-three or four years old. He was slightly older than me, wore a headscarf, left his long hair loose over his shoulders, carried a long knife at his waist, and was dressed entirely according to the customs of the Heavenly Kingdom. He had me change into a similar outfit and gave me a token to help with passage, instructing me not to wander off alone. I was both astonished and nervous upon entering the Heavenly Kingdom’s camp. Ah Leung and I spent a night in the town. He was a man of few words. When I asked him about the scar on his forehead, he said, “My village was considered a nest of rebels by that bastard Ye Mingchen, who slaughtered everybody including my four family members. Only I survived.” I enlightened him that Ye Mingchen, the governor of Kwangtung and Kwangsi, had been captured by the British and died in India. Hearing this, Ah Leung sneered and said, “Serves him right.!” But his resentment remained. “His death was too easy for him.” I then asked him about the numerous corpses outside the town and whether the Taiping army randomly killed people. He responded, “No, the soldiers who initially joined were very disciplined and absolutely would not indiscriminately murder innocent people. However, due to a lack of troops, we enlisted quite a few local bandits. These individuals have no qualms about killing. But they are nothing compared to the brutal Xiang army. Those bastards are known for their rape and plunder, they are even worse than beasts!” I further inquired, “Do you truly believe in Jesus Christ?” He affirmed, “Of course I believe in the Heavenly King’s Elder Brother in Heaven. He would help us kill those Qing demons.” I had my doubts about the Heavenly King’s distortion of Christian doctrine, but I kept silent and did not express my suspicions at that time.

The following day, we set off for Suzhou and saw troops of the Heavenly Kingdom mobilizing constantly along the way, which was an impressive sight. The amount of movable type was quite substantial and rather heavy. We transported them on two ox carts, moving slowly with frequent stops, and it took two days to arrive. Suzhou was a key regional stronghold, with very robust defense works. During the Heavenly Capital Incident, all the Kings from the four corners of the kingdom had died. The Wing King Shi Dakai fled, while Loyal King Li Xiucheng and Heroic King Chen Yucheng, both national heroes, had repeatedly defeated the Qing troops. However, the Heroic King was later lured and killed. Loyal King repeatedly made military mistakes and was confined to the Heavenly Capital. Without any more capable generals in the outer strongholds, they could only defend themselves and had no strength to relieve the siege in the Heavenly Capital. We stayed in Suzhou for more than a month, until one day, Ah Leung told me there was an emergency outside the city and we had to retreat immediately. Consequently, we took with us the two sets of movable type and went to Changzhou to wait for news from King Gan.

Upon arriving in Changzhou and staying for over ten days, one day, the commanding officer Chen Kunshu made a surprise visit to my guest house. He said he found out I was from the Missionary Society that was transporting movable type for King Gan and wanted to see what was going on. Ah Leung had told me earlier that Chen was originally from Guiping, Kwangsi, a veteran of the current dynasty and an old minister since the Jintian Uprising. He had fought under the Loyal King Li Xiucheng for many years, accumulating considerable merit and was awarded the title of Protector King. Back when he was stationed in Suzhou, he had met with visiting missionaries and got along with them very well. Chen was very surprised to see that I was very young, and said, “The type has been delivered, you can leave. Why do you still stay for long?” I replied, “I want to personally give it to King Gan to prevent any mistakes, this is our agreement.” He said dismissively, “They are just a pile of lead pieces, why take such risks?” I replied, “As long as there are words, human will exist. If the words cease to exist, so will human.” He laughed heartily and said, “I have never seen anyone that obsessed with words.” I said, “King Gan and I knew each other in Hong Kong’s missionary station. We are brothers in Christ.” He said seriously, “We both worship the same God. You have overcome all obstacles to deliver these lead types. There must be God’s will in it. If you need anything, just ask." Two days later, the Protector King sent a message saying that King Gan had left the Heavenly Capital, recruiting troops everywhere, and now was in Huzhou. Meanwhile, the situation in Nanchang was dire and there was no support. The Huai army of 100,000 and the Ever Victorious army of thousands had already laid siege to Suzhou. Chen instructed me to go to Huzhou to see King Gan, and dispatched ten guards to escort me.

Three days later, Ah Leung and I arrived in Huzhou and finally met with King Gan. Upon first meeting him, we were received at the royal palace in Huzhou. There was a line of soldiers in the entrance passage of the palace, beating gongs and blowing bugles, creating a grand spectacle. In the hall, lanterns were festooned everywhere. King Gan, wearing a golden crown and a yellow robe, stood majestically on the dais, exuding an impressive aura. I had never witnessed such a scene before and was at a loss. Just as I was wondering whether or not to kneel, King Gan suddenly stepped forward, greeted me with a handshake as per Western custom, invited me to sit down and had someone serve tea, treating me as an honored guest. The courtesy made me feel even more uncomfortable, and I had no choice but to behave appropriately. He explained to the others my purpose for visiting and expressed thanks to the London Missionary Society. After his speech, King Gan dismissed the officials and only a few maidservants remained. He took off his crown, removed his robe, and sat down opposite me. It was then that I realized that everything before was official ceremony. King Gan resumed his informal persona, Big Brother Hong, and said warmly, “Ah Fuk, I didn’t think we’d have the chance to meet again.” I replied, “Mr. Legge, Mr. Ho, Mr. Wong and others, they all miss you.” Brother Hong was overjoyed and said, “I miss everyone too.” He then proceeded to ask detailed questions about our colleagues back at the station, and I responded one by one. The memory of our shared past times revisited my heart vividly. After a long chat, Brother Hong got up, took my hand, and led me to an inner chamber to inspect the movable type. They were not stored in a warehouse, but placed in the hall like treasured artifacts. The lead type was still held in wooden boxes and displayed on a table. Brother Hong opened a box, picked out a couple of typefaces, looked at them closely, seemed very satisfied. I then tentatively told him about the preparations of the printing house, and offered to teach the techniques to the one who will be in charge. His face changed suddenly and said angrily, “The printing press we ordered was intercepted by Qing soldiers on its way here, and sank to the bottom of the river with the boat.” I felt a sense of bad omen, but I didn’t let it dampen my spirits, comforting him by saying, “We can always buy another printing machine, but it’s essential to protect the movable type.” Brother Hong nodded with a bitter smile.

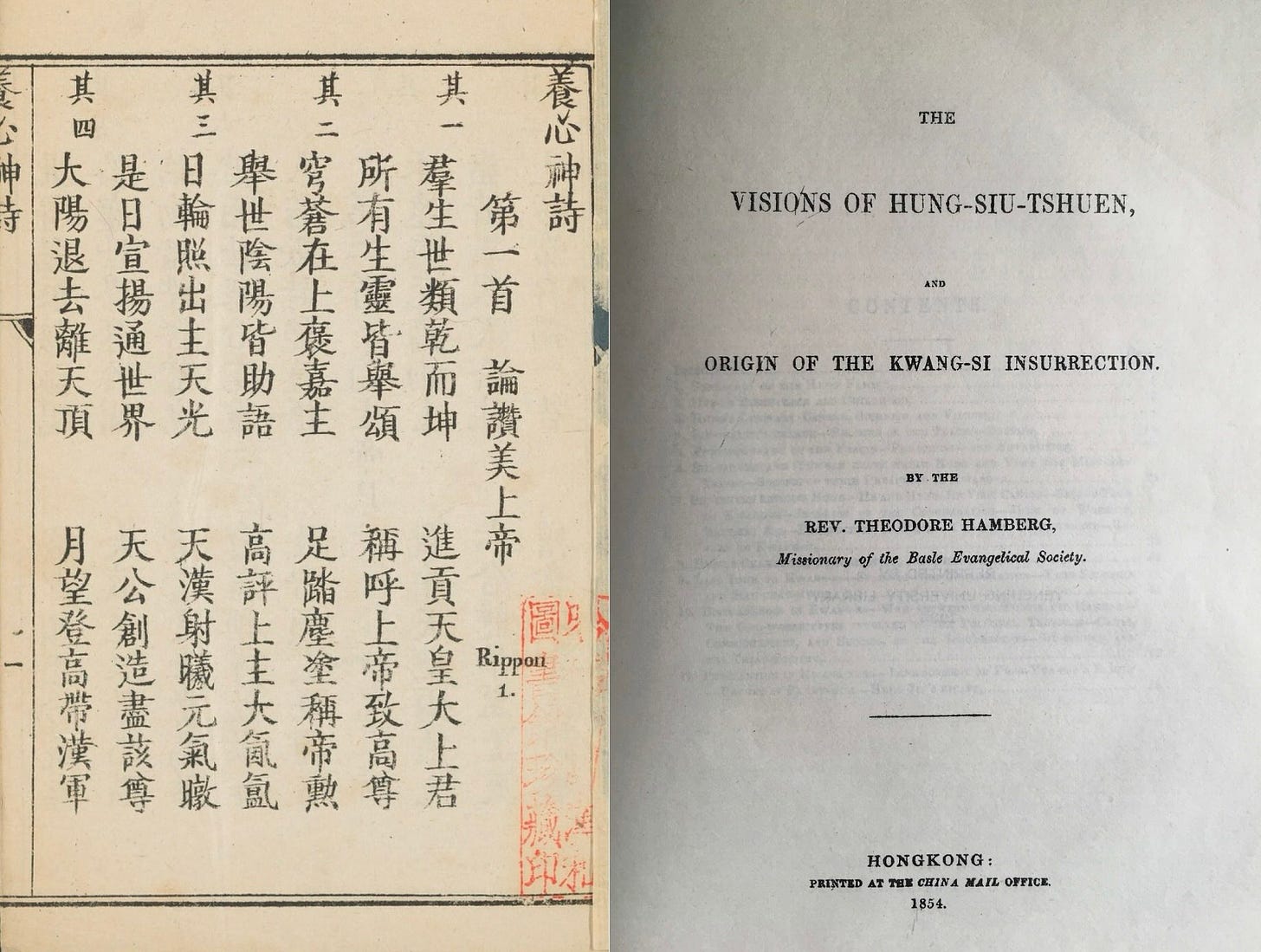

At nightfall, Brother Hong set a feast in the small room, creating a carefree atmosphere. Before we started eating, he suggested we pray together. I joined him standing in front of the table, and he led the prayer, praising God, believing in Jesus, and asking the Holy Spirit to descend into our hearts. Brother Hong also led the singing of three hymns from Hymns for Nourishing the Heart compiled by Mr. Medhurst. The first hymn states, ‘All creatures of the universe, pay tribute to the Heavenly Emperor, all living beings praise him, calling God the highest honour.” The second says, “Lord of the dome above, stepping on the dust signifies imperial merit, all things under the sun assist in the praise, highly comment on the providence of the Lord.” The third, “The sun shines the Lord’s heavenly light, celestial bodies radiating vitality, this day proclaimed to the world, the creation of the Heavenly Lord should be honoured.” After prayer, we sat down again, raised our tea, and wished each other well, for Taiping Heavenly Kingdom prohibited alcohol. Brother Hong asked if I had been baptized, I replied not yet, expressing the doubts in my heart. He said, “Westerners have brought the gospel of the Heavenly Kingdom, and we should be grateful. However, they invaded our land, sold opium, and poisoned our people, which is unforgivable. They initially had good intentions towards our country, but later they colluded with the Qing dynasty, attacking from both sides, which is despicable.’ I then told him that Mr. Legge opposed the British use of arms. Brother Hong was moved upon hearing this, saying, “Brother Legge is a true believer, he has both love and righteousness.” He further added, “Ah Fuk, let me tell you, when I was in Hong Kong, it was the happiest time of my life.” After saying this, he fell silent, seemingly lost in thought.

The few days after passed without anything happening. I sat alone in my room, where a day felt like a year. Suddenly one morning, King Gan summoned me to the hall where the movable type was stored. Big Brother Hong was in casual dress, without any courtier beside him, his expression full of worry and unease, very different from before. He seemed to want to say something, but hesitated until he finally spoke, "Ah Fuk, Suzhou has fallen, followed by Changzhou and Hangzhou. Li Hongzhang has the aid of the Westerners’ Ever Victorious Army, we can’t hold out. Zeng Guofan’s Xiang Army has already heavily surrounded the Heavenly Capital. The Heavenly King had sent me out of the capital, originally to organize a campaign to rally support, but everyone is now in peril, there’s no response at all. The Heavenly Capital is about to run out of bullets and food, what’s the point of us keeping these lead types. Ah Fuk, I know these types are the fruit of your labour, please forgive me, I have decided to use them to cast bullets. If one bullet can kill one Qing soldier, we can potentially kill ten thousand. Even if not ten thousand, a thousand will do. However, no matter how many we kill, it’s not going to change the outcome. Everything can’t be turned around.” I was speechless. I picked out the characters Lee Nga Kok, Cham Ma Si, Ho Jun Sin, Wong Shing, Wat Ong, Dai Fuk, and Hong Ren Gan from the wooden box, handed them over, and said, “Big Brother, keep these few characters as a memento.” Upon hearing this, Brother Hong was overcome with sadness. That night, several furnaces were set up in the courtyard of the palace, where I personally threw all the movable type in, shedding silent tears with every piece.

The following day, accompanied by Ah Leung, I left Huzhou and headed east. Brother Hong personally came to see me off, and before parting, he said, “Ah Fuk, pray for me.” Upon reaching the border of the Qing dynasty, Ah Leung had prepared a boat. We said our heartfelt goodbyes, and I then disguised myself by tying my hair into braids and changing my clothes and slipped away on the boat. Halfway through the journey, I was captured by Qing soldiers. I showed them the letter from Mr. Muirhead, claiming that I had traveled from the Shanghai Missionary Station to contact believers in the inland areas a month ago and had been stranded in rural areas to avoid war. The officials were suspicious, but feared offending westerners, and did not dare to act hastily. After being detained for more than a month, fortunately, the Society worked tirelessly to secure a guarantee from the British Consulate, and I was finally released. Upon arriving in Shanghai, I fell seriously ill and had to recuperate for several months before I was able to return to Hong Kong. By that time, it was already the end of 1864.

What happened afterwards?

What happened to whom?

To King Gan and others.

Unbearable to recall.

Heng Yi wants to know.

Really? Alright, let me talk more about it.

In April of the third year of Tongzhi, Changzhou fell. The Protector King Chen Kunshu steadfastly refused to surrender, fighting to the last soldier. Later in the same month, Heavenly King Hong Xiuquan starved to death by eating grass, and young Heavenly King Hong Tianguifu succeeded the throne. In June, the Xiang Army attacked and captured the Heavenly Capital, indiscriminately slaughtering both military and civilian inhabitants. Women under the age of forty were captured and carried off, and young children were stabbed for amusement, with the death toll amounting to two to three hundred thousand. At the time of the city’s breach, Loyal King Li Xiucheng was captured, but the young Heavenly King managed to flee, later to be found by King Gan, who took him south. In September, the troops of King Gan were ambushed by Qing soldiers in Shicheng, Jiangxi, and Hong Rengan was captured, subsequently executed in Nanchang. The young Heavenly King was also captured and sentenced to death by slow slicing (death by a thousand cuts). In his own confession, Hong Rengan claimed to emulate Wen Tianxiang’s noble martyrdom, bravely facing execution. However, he referred to Western missionaries as barbarians and did not testify to the Christian faith. Mr. Legge once lamented, “If Hong Rengan had listened to me and stayed in Hong Kong, his head would still be on his shoulders today.”

I have nothing more to say.