Six Records of a Resurrected Life

II. Apprenticeship

Heng Yi, my last letter talked about a significant decision in my life, which is to become a printing apprentice. This matter might not be of much interest to you, but it is related to the various fortunes of both of us, so I will give a brief account of it. It was when my apprenticeship was completed that I met you again. I want to share with you my feelings and circumstances at that time. As for the subsequent misunderstandings and missed opportunities, they were simply impossible to foresee. Could the whims of the world really be the will of God?

When I first entered the printing house, there were a total of ten craftsmen, divided into character carving, type molding and casting, plate layout, printing, and binding. Following the advice of Mr. Wong Shing, I started learning typography and page layout. But if I want to be promoted in the future, I need to master other processes as well. The reason Mr. Wong Shing said this was because he saw that I had already studied at the college for a few years and my Chinese and English skills were superior to those of the average worker. Mr. Wong Shing was originally from Heung Shan County, Kwangtung. He once attended the Morrison Memorial School, then went to study in the United States of America with two other classmates. Although he had to return to Hong Kong due to illness, his Western education was still top-notch among the local Chinese. After returning to Hong Kong, he practiced printing at the The China Mail for a year and a half before he became the head of the Anglo-Chinese College Printing House. It was said that the local court wanted to hire Mr. Wong as a translator at a high salary of 120 dollars, but he preferred to serve at the college printing house for a monthly salary of 30 dollars. His choice was highly praised by the staff in the mission station.

The supervisor of the printing house was Mr. Chalmers, and Mr. Wong Shing was the superintendent, under whom was Mr. Wong Muk, the head of the craftsmen. Among all the craftsmen, Mr. Wong Muk was the most senior, having previously served in the printing house in Singapore, before moving along with the College to Hong Kong. Mr. Wong Shing was not personally involved in the daily printing work, and the training of apprentices was also the responsibility of Mr. Wong Muk, who was my master. Apprenticeship was always more about suffering than joy - masters were often harsh and abusive, keeping their skills a secret - as was occasionally reported. Fortunately, Master Wong Muk was strict but fair, and was willing to share his knowledge and skills. In addition, the demand for the new translation of the Bible was great, and the typefaces were selling well. Everyone had to devote their full efforts, with no room for idle or neglect. I took this opportunity to hone my skills. When I first joined, there were only two printing presses. One of them was quite old, a relic left over from the Malacca missionary station forty years ago. Two years later, a third new press was purchased. In subsequent years, the fourth and fifth were gradually added, greatly increasing production. This was necessary to print the Chinese Classics translated by Mr. Legge.

Every day I kept company with characters, feeling excited and unaware of hardship. Yet, I also felt apprehensive about acquiring the expertise in this field. As a beginner, the first thing to learn was to dissemble a page and return the typefaces to their right places on the shelf. It took me a long time to find where they belonged. Then I learned to arrange the characters and lay out the pages, but the order was often in chaos and did not form sentences. Finally, when a page was assembled, it was loaded into the machine, inked and printed. The appearance of characters and sentences on paper was like magic, or a miraculous transformation. The joy was beyond words. After typesetting, I also learned to cast typefaces. We had two sets of Chinese lead movable type, one large and one small, both were first invented in Malacca by a past missionary, Mr. Samuel Dyer. Mr. Dyer died before achieving his ambitions, but his successors carried on. As I heard, it was only completed a few years before, about the time I started my studies at the college. Each set of movable type had over a hundred thousand characters, which were sorted by radical strokes and classified as commonly used and rarely used. They were placed on wooden shelves in categories for easy access during use. I think back to the days when I collected printed papers and wondered how the characters on them got there. Now, each piece of movable type was born in my hands, and each one of them gave birth to more words. From droplets to streams, all rivers run to the sea, converging in a vast ocean of characters and huge waves of knowledge. Try to imagine how magnificent a scene that is! Oh, whenever I talk about my job, I can’t stop, just like a long and smelly foot-wrapping cloth. I hope you don’t mind.

After I joined the printing house, I still lived in the college dormitory. However, the mission building, which had been built for more than a decade, was somewhat deteriorated and leaky. Mr. Legge had repeatedly applied to the London headquarters for reconstruction, but to no avail. The only solution was to make minor renovations and turn the lower building into a residence for Mr. Ho Tsun-shin’s family, while Mr. Legge moved to the upper building. The old student dormitories and classrooms were converted into guest rooms, as well as a more spacious dining hall. Years later, a part of the land near Hollywood Road was sold, and a new printing house was built next to the upper building. The address was changed to Aberdeen Street. You must have heard and witnessed all these changes, since your home was just a stone’s throw away. The peculiar thing is that though we were so close to each other, we had never met these past few years. Only once did I catch a glimpse of your back in the market clinic, but you didn’t see me.

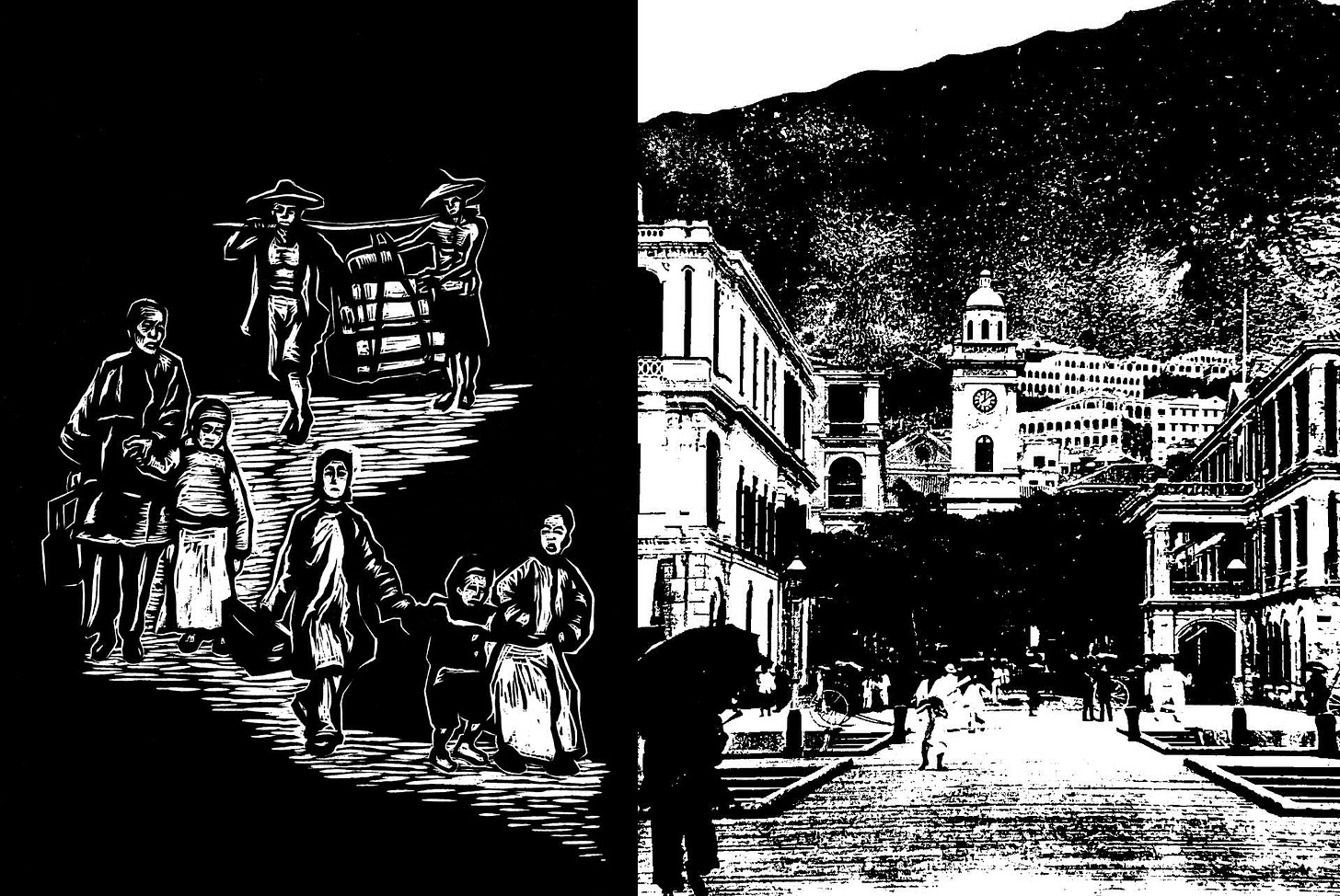

In October of the previous year, the Arrow Incident occurred, which provoked the people of Canton to attack foreigners ferociously. The Thirteen Factories were completely burnt down, prompting the British naval forces to invade Canton. Anti-British sentiment was high in Kwangtung and the missionaries stationed in Canton also retreated to Hong Kong. At that time, calls to kill foreigners and traitors were on the rise, and there was even rumors of an impending attack on the City of Victoria, causing panic among the inhabitants. Many Chinese businessmen began to flee the port. In January of the following year, the Poisoned Bread Incident happened. I only remember that on that morning, after I and the other Chinese workers had breakfast, we heard the news that Mr. Legge had been poisoned. Afterwards, we learned that many Westerners in the city had also eaten the poisoned bread and felt unwell. Luckily, Mr. Legge’s poisoning was not severe and he slowly recovered after vomiting. The authorities tested the bread and found it contained arsenic, pointing the finger at Yu Shing Store, the only Western bakery in the city. Coincidentally, the store owner, Cheung Pui Lam, and his family left for Macao that morning, making him a prime suspect and he was immediately arrested. After investigation, it was confirmed that the incident was instigated by anti-foreign forces bribing bakery employees and the owner was unaware. However, Mr. Cheung was still fined and deported. On the day of the incident, Mr. Wong Shing went to the hospital to visit his western friend who was poisoned, and sent me to the Central Pier to pick up a passenger. The expected arrival Mr. Wong Foon was a classmate who had studied abroad with Mr. Wong Shing. As I looked out from the pier, I saw a Chinese man in a western suit and hat standing on a barge, looking elegant and refined. I guessed he must be Mr. Wong Foon. When he got ashore, I went up and greeted him, only to find out he could hardly speak the local dialect due to having left his hometown at a young age.

Mr. Wong Foon completed his middle school education in the United States, and then studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. After graduating, he became a doctor missionary of the London Missionary Society and was assigned to work in Canton. However, due to the unstable situation in Canton, he settled down in Hong Kong first to wait for the right opportunity. During his stay in Hong Kong, he set up a free clinic next to the Lower Market Church. To avoid rejection and attacks from locals, he dressed in Chinese clothes, wore a fake wig braid, but his language skills were somewhat inadequate and he needed the help of an interpreter from time to time. The church clinic often had preachers speaking to patients, with Brother Hong Rengan being the current one. One day, I went to the clinic to deliver missionary brochures to Brother Hong. As soon as I entered the door, I saw two women, one old and one young, who looked like mother and daughter, sitting in front of the doctor’s desk for a consultation. The daughter was dressed in plain Chinese clothes, was thin and looked like an ordinary local girl, except her braided hair was brown and the skin on the back of her neck was snow white, which set her apart. For some reason, I suddenly felt a burning pain in my left arm and almost dropped the brochures. Brother Hong took the brochures, distributed them to the patients, and continued to preach the Gospel loudly. With nothing to do and not wanting to stay too long, I left. I wandered back and forth on the streets, unsure of what to do. Suddenly, I thought that if you came out and saw me there, and I didn’t know what to say, it would be worse, so I turned around and left in a hurry.

Brother Hong Rengan, from Fa County, Kwangtung, was the cousin of Hong Xiuquan, the Heavenly King of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. Initially, Hong Xiuquan, Feng Yunshan, and Hong Rengan together founded the God Worshipping Society. During the Jintian Uprising in Kwangsi, Hong Rengan was in Kwangtung and was unable to participate. He later attempted several times to join, but was blocked by the Qing soldiers and could not succeed. He then fled to Hong Kong and joined the Basel Mission under the tutorship of Reverend Theodore Hamberg. After the establishment of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom capital in Jinning, he tried to sneak into its occupied territories, but to no avail. He stayed at the London Society Shanghai preaching station for more than a year. He then returned to Hong Kong and was taken under the wing of Mr. Legge, who let him teach Chinese literature at Anglo-Chinese College and help spread the Gospel among the Chinese. He also had a shared interest in astronomy and mathematics with Mr. Chalmers, and they often studied together. In the few years before, Mr. Legge lived alone as a widower, throwing himself into his work. However, after the arrival of Brother Hong, they became close friends. As Mr. Legge expressed, Mr. Hong is sincere, passionate, intelligent, and deeply devout in his faith, and will have a great impact in his missionary work.

When I first met Big Brother Hong, I was still a student at the college. I found him to be generous, enthusiastic, and extraordinary, different from other teachers. At that time, among the Chinese missionaries, Mr. Ho Tsun-shin was the best speaker and leader, the pillar of the Chinese church. The elderly Mr. Wat Ong was the most senior, but he was somewhat impetuous and his mood fluctuated. Brother Hong’s arrival greatly enhanced the prestige of the church and brought an unprecedented vitality. One day, I went to the library to read alone, casually flipping through a book called Good Words to Admonish the World, when I suddenly saw Teacher Hong approaching. I hurriedly greeted him, but he told me to call him Big Brother Hong. He asked me what book I was reading. I showed him the cover and he immediately widened his eyes and raised his eyebrows, exclaiming, “This is the scripture that brought enlightenment to the Heavenly King!” He then started to passionately recount the struggles he and his brother went through when they founded their own religion. He talked about smashing idols, killing demons, gritting his teeth and full of pride, leaving me in awe and admiration. This was the first time I heard someone openly declare that the Qing Dynasty must perish, and my heart was trembling. Afterward, whenever I had free time, I would talk to Big Brother Hong, listen to his heroic statements, and participate in worship sessions presided by him. My faith gradually grew through this influence. This part of Brother Hong’s story was once narrated by Mr. Theodore Hamberg in English, in a book entitled The Visions of Hung Siu-Tshuen, and Origin of the Kwang-Si Insurrection. The original intention was to use the proceeds from the book sales to fund Brother Hong, but unfortunately, Mr. Hamberg died of illness before the book was published, which was truly regrettable.

The brief encounter with you at the clinic made me feel uneasy for some unknown reason. On several occasions, I found myself deliberately taking detours past the photo studio without any reason, yet, never daring to linger, only casting a brief glance, with no action taken. Despite this, the display window revealed two more portraits of a girl even more stunning than before, which made my heart flutter uncontrollably. Later, when I spoke with Big Brother Hong, I discovered surprisingly that he knew your background and proceeded to tell me your story. As he explained, you and your mother had been going to the clinic for over a month due to your mother’s illness, not yours. Because your appearance differed from local girls, he was very curious and had extensive conversations with your mother. He learned that you were the daughter of the owner of the photo studio on Flower Market Street. Why you were born with a different color, he dared not ask directly, but it was suspicious indeed. He also found out that you studied at the college when you were young, so he enquired about your past from Mr. Legge, who revealed a little-known history. According to Mr. Legge, at the time when the port was built, the law and order was poor. Not only were there rampant local pirates who frequently killed Westerners, but also, incidents of western sailors and soldiers trespassing and harming the Chinese were not uncommon. Once, a village maiden from Wong Chuk Hang was violated by a foreign sailor and the culprit escaped afterward. The maiden got pregnant and gave birth to a girl. She was shamed by the villagers, had nowhere to go, and in her unbearable humiliation, committed suicide by hanging herself. The maiden had a sister who was married to a Chinese photographer, Lai Ah Chang. Overwhelmed with grief for her sister and not being able to bear the thought of the girl growing up motherless, she adopted the baby girl and called her Lai Heng Yi. When the Westerners living in Hong Kong heard about this, they all pitied her unfortunate fate and did their best to help. Innocent as the girl was, she was seen as an illegitimate child in the eyes of the locals and was thus subjected to relentless ridicule. Attending a charity school established by Westerners, she was also ostracized by her classmates, and eventually dropped out halfway.

I’ve mentioned your past above, not to remind you of your miserable past, but to let you know that there are people in the world who see no shame in this. As Brother Hong said, “Yahweh is indeed God of justice. Those who suffer in this world will eventually be exalted, and those who bully the weak will be humiliated. The Kingdom of Heaven is coming, where the righteous will enjoy eternal blessings while those who wickedly commit evil will go to hell for eternal punishment.” I sincerely believe that the good and evil in the world will be judged fairly. And you will return to our Heavenly Father's embrace with a pure body and heart. I only pray that I can also resist the sins of the world, remain innocent and enjoy eternal happiness with you. I believe in God because I believe God will protect you and save you. However, I don’t know what I can do.

When it comes to faith, the person who impacted me the most was Brother Hong, followed by Mr. Wat Ong. I still remember when I first started school, the hymns for morning and evening prayers were led by Mr. Wat. His deep voice was powerful enough to stir the soul. At that time, Mr. Wat was already in his seventies, like a grandfather to the students. However, everyone was a bit afraid of him, because he did not appear very kindly and hardly spoke. He was baptized by the pioneer, Mr. Morrison, but always took on a secondary role at the evangelistic stations. Unlike Mr. Ho or Brother Hong, who were elegant in demeanor, he seldom presided over worship services, dedicating himself solely to street preaching. His footprints could be found in every corner of the city. He always carried a bag of missionary booklets, visited households, exchanged a few words, stayed longer if the person was friendly, skipped over if not so. He never forced anyone or had any arguments. His journeys sometimes extended to rural villages, east to Shau Kei Wan, south to Stanley, and north to the villages across the bay in Kowloon. Although I was not very close to Mr. Wat, I did accompany him on several occasions to distribute books. I was busy with my printing work, but since I was preparing to join the church, Mr. Ho also assigned me some missionary tasks, so that I could learn some principles from my seniors. However, I didn’t hear much preaching from Mr. Wat, most of his teachings were about being a good person and doing good deeds. One day I asked Mr. Wat why he did not preach more about repentance of worshiping false gods and Buddhas, and eternal punishment in hell. He said, “Chinese people don’t like to hear such things, it’s better to talk more about love, they like to listen to that, and then they would believe in Jesus Christ.” After speaking, he picked out a few flyers from his bag, gave them to me and said, “These are a few chapters of the Bible that I like to preach the most, and people like to hear them the most. Even those who don’t like to listen, if I preach these chapters, they will listen.” So you know, later on, the scriptures I printed for you to read were mostly selected from here, following the intent of Mr. Wat.

In the eighth year of the Xianfeng era, Mr. Legge returned home for a vacation. Before he left, he sternly advised Brother Hong to stay in Hong Kong and avoid getting involved in any dangerous activities. However, not long after, Brother Hong bid farewell to Mr. Chalmers, expressing his desire to go north to the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom to spread the true doctrine of Christ. Mr. Chalmers not only did not oppose, but also generously funded Brother Hong’s travel expenses. At that time, most of the missionaries of the London Missionary Society showed sympathy for the rebels with the hope that Christianity could spread widely in China. Brother Hong Rengan, with his firm and orthodox faith, was the best choice to accomplish this endeavor. Unexpectedly, news came a year later that Brother Hong was appointed as King Gan, assisting the Heavenly King in managing the government. Brother Hong could finally realize his ambition, which was a good thing, but it is also regrettable that he ended his ties with Hong Kong. As for the precariousness of the current situation and the numerous challenges ahead, they were aspects that I was unable to contemplate at the moment.

Mr. Legge returned to Hong Kong in September of the following year, bringing with him his new wife and her daughter from a previous marriage, along with his own two daughters. The new Mrs. Legge was very sociable, and from then on, the house was filled with frequent banquets and a never-ending stream of guests, creating a lively atmosphere. In addition to their existing daughters, younger siblings were born in quick succession, and the sounds of children playing and laughing could be heard every day. The scene at the missionary building was utterly different from the years when we were students. Mr. Legge also appeared rejuvenated, as if winter had turned into spring. Apart from his missionary work, he also participated in public affairs, promoting education, and devoted himself to studying. In the subsequent two years, the English translations of the Confucian Analects, The Great Learning, and The Doctrine of the Mean, and The Works of Mencius gradually went to press, and we printers were kept extremely busy. As my English is decent, I was responsible for typesetting Mr. Legge’s works. While handling the characters, I took the opportunity to read them first. Despite my lack of talent, familiarity with classics, or learning in poetry, I could tell that Mr. Legge put in a lot of effort. Whether investigating historical facts, collating different versions, commenting on different schools of thought, or even analysis of the principles, every detail was attended to. Regarding the teachings of the Confucian sages, he was generally approving, and often praised them. However, he also criticized them, because they ultimately fell short of Christianity. Albeit I am not smart and could not argue, I had difficulty totally accepting this, and I felt a certain unease.

One day, while delivering religious books to the chapel in the market, I was suddenly attacked from behind on my way through Kau U Fong. Using my book bag as a shield, I held the villain off for a while until he suddenly stopped. As we both looked at each other in astonishment, I recognized the assailant to be Ah Wong. Since I had moved to Hong Kong for my studies seven years ago, I had kept in touch with Ah Wong, especially during my early summer vacations back to Monk Kok Village. However, after becoming an apprentice, my visits back home had become irregular—sometimes twice a month, other times once in two months. Sometimes I would stay for one night, other times just half a day, and my encounters with Ah Wong had become increasingly rare and distant. I had heard that Ah Wong had started causing trouble with a group of hooligans and was consequently evicted by my uncle. I had no idea that he had fled to Hong Kong and was waiting for an opportunity to strike. When he saw that it was me, he was at first embarrassed but then became angry, cursing me as a traitor. Despite feeling wronged, I restrained my anger and invited him to the tea house to clear up the misunderstanding. Faced with my goodwill, Ah Wong couldn’t act out and agreed to sit down for a chat. He told me that our hometown had recently become a British territory and that he and his comrades were plotting to resist and expel the barbarians and execute the traitors. He rebuked me vehemently, “The Red-haired Ghosts have seized our Kowloon. How can you just stand by? Surely, it must be because there’s money to be made, benefits to be taken, and you can afford to let our home be taken over?” I felt ashamed, but also disagreed with him, arguing about whether the ruling Qing dynasty, which was another ethnic group that was autocratic, corrupt, and exploiting the people for its self-interest, was worth it to risk our own lives for. We ended up sticking to our own points of view and parted on bad terms.

After going back, I pondered for a long time and decided to seek advice from Mr. Legge. He was proofreading manuscripts in his study. When he saw me, he thought I was coming to urge him for finished proofs. I explained my intention, saying I wanted to discuss the matter of my forthcoming baptism. Mr. Legge said, “Mr. Ho has already talked to me, and your pre-baptism question and answer were very good.” I replied, “But I still have doubts.” He asked, “What doubts?” I said, “Mr. Legge, is the Beijing Treaty right or wrong?” He did not expect such a question and was at a loss for words. I further inquired, “Is it right for Westerners to sell opium to the Chinese?” This time he immediately responded, no. I continued, “After selling opium, is it right for them to invade and occupy the land and force the treaty?” He replied, no. I then exclaimed in confusion, “Mr. Legge, I don’t understand, why would the most righteous God allow such things, and how should Christians respond?” Mr. Legge’s face was flushed, he lightly tapped the table with the goose feather pen in his hand, and sighed, “Ah Fuk, I can tell you, the Missionary Society has always opposed the opium trade and does not support using war to resolve disputes. Even though we call ourselves Christian nations, many politicians and businessmen are not eligible to call themselves Christians. I’m really sorry about this. I know that when things like this happen, many Chinese people hate us and don’t believe in our religion. But no one can fully understand God’s will. We can only believe in him and insist on being loving.” Looking at his expression, I believed his words were sincere, but I could only say, “Mr. Legge, I want to wait a bit longer. Under the current circumstances, I cannot receive baptism with peace of mind.” He nodded and said, “Baptism is foremost about faith. If the faith is not enough, there should be no rush. May Jesus Christ bless you!” That was how my first baptism attempt failed.

The matter of baptism was temporarily put off. As if a heavy stone was lifted off my heart, I devoted myself without distraction to typesetting day and night, immersed in a sea of words, unconcerned with worldly matters. One day during a break, Master Wong Muk instructed me to deliver some goods. I took the delivery order and saw that the items being printed were some shop notices, and the recipient was Ah Chang Photo Studio on Flower Market Street. By now I had heard that in the early days of the colony, a Western photographer named Robertson opened a photo studio in Central and hired Ah Chang as an assistant. Robertson had no family and he died suddenly of typhoid. Ah Chang then took over the business, specializing in photos of local street scenes and portraits of Chinese men and women. This is how your father came to his profession. When I arrived at the photo studio with the printed items, I walked through the door with a legitimate reason. I found the entrance area full of photos and photo frames, and deeper within, a photo studio was set up with cameras, lighting devices, and various kinds of props like Chinese and Western chairs, candle stands, and curtains. There was a skylight at top of the studio for lighting, which was currently closed and covered with bamboo blinds. Seeing nobody in the shop, I cried out delivery. A curtain leading to the living room behind the store immediately lifted, and your figure emerged from the darkness, looking up, lightly brushing your bangs aside, like a flower blooming out of the fog. The faded and blurred face from many years ago was as if developing into a photograph at this moment, vividly in front of my eyes. I asked, “Is the boss around?” You replied, “Dad’s out for a while.” I put the goods on the counter, asked about your mother, only to hear you say, “Mom’s passed away.” I asked, “When? I saw you two at the clinic not long ago.” You said, “Doctor Wong got transferred, and soon after, Mom didn’t make it.” I was speechless and didn’t know how to reply. After a while, you asked, “Are you still at the college?” Seeing that you really recognized me, my heart leapt with joy. I nodded and said, “I stayed as an apprentice and work on movable type printing.” You picked up the prints, gently stroking them with your fingers, and asked, “Did you print these?” I shook my head and said, “No, I print Bibles.” You looked up as if remembering something and said, “Oh, Bible.” I then asked, “Have you ever read the Bible?” You shook your head and said, “Haven’t read it in a long time, can’t remember it.” So I said, “I’ll bring you some Bible pamphlets when I’ve got free time.” You smiled slightly, neither agreeing nor disagreeing. I then asked, “Have you been reading since you left the college?” You thought for a moment and said, “I’ve been learning some English. Dad says it’s for dealing with the Westerners in the future.” I echoed your statement, “Your shop must be popular among Westerners.” You shrugged, glanced at the clock on the wall, and said, “My dad will be back soon.” So I said, “Then I should go.” As I was about to leave, I gathered the courage to ask, “Will we see each other again?’ You seemed a little surprised, but replied quickly, “Tomorrow at noon, Central Post Office.” I understood and left.

The next day at noon, during the print house lunch break, I excused myself and rushed straight to the Central Post Office. I saw you standing in front of the counter, handling your business. Today, you wore a jade-blue western dress, with which, viewed from behind, you looked no different from a foreign lady. Within a few minutes, you finished your errand, glanced left and right, then walked towards me. You said you had just sent some items for your father, bought some stamps, and had some spare time to walk around. We then left the post office and strolled along the streets. We passed by a bakery, and I asked if you’d like a piece of pancake. You nodded slightly, so I bought two, and we ate as we walked, ending up by the seashore. Along the coast, a plethora of boats covered the sea; coolies were busy loading and unloading goods, many of which I assumed were opium. I thought of Ah Wong and couldn’t help but glance hurriedly around, fearing a sudden attack. You stood gracefully on the edge of the Praya, your untied hair billowing in the wind. I asked your age, to which you said fourteen, five years younger than me. But judging by your slim and tall figure, there was a stark difference from a few years ago, I wondered if it was due to heredity. It was as if you read my mind and asked, “You already know about my background, don’t you?” My face turned red as I nodded. You continued, “My father is not my father, my mother is not my mother. There is no difference from being an orphan. I have been bullied by classmates at school, and by parents at home, not knowing where to find peace.” By the end, you choked up and two lines of tears ran down your face. The wind kept getting stronger and the waves crashed loudly against the shore. If at that moment you had jumped into the sea, I believe I would have followed you. Wiping your tears, you lowered your head and asked, “Can you take me away?” I was unprepared, my heart shook, and I stammered “I’m just a rookie typesetter, and you’re the daughter of the owner of a photo studio. I’m afraid your father won't consent.” You bit your lip and said, “You’re right, my dad will never allow it. He always says, ‘rare goods are valuable’.” At the time I didn’t understand your words, thinking it was just a momentary emotional outburst. We stood silently for a while, with storm clouds gathering overhead, hinting at the coming of the first summer typhoon of the year. I suggested, “It’s about to rain, let’s go home.” I walked with you to the end of the Flower Market Street. You looked at me and said with a resolute voice, “Please forget what I said before, never come find me again, just consider it a dream I spoke.” With that, you turned away, crossed the road with brisk steps. The heavy rain started to fall, separating you and me.

Let’s stop here for today.